- Foundational Land Transfers: The 17th-century land deeds between Native American leaders and English settlers (such as Cheesechamut’s deed and the Miantonomi deed of 1642) form the legal and historical backbone of Warwick’s existence, determining the town’s geographic boundaries and legitimacy.

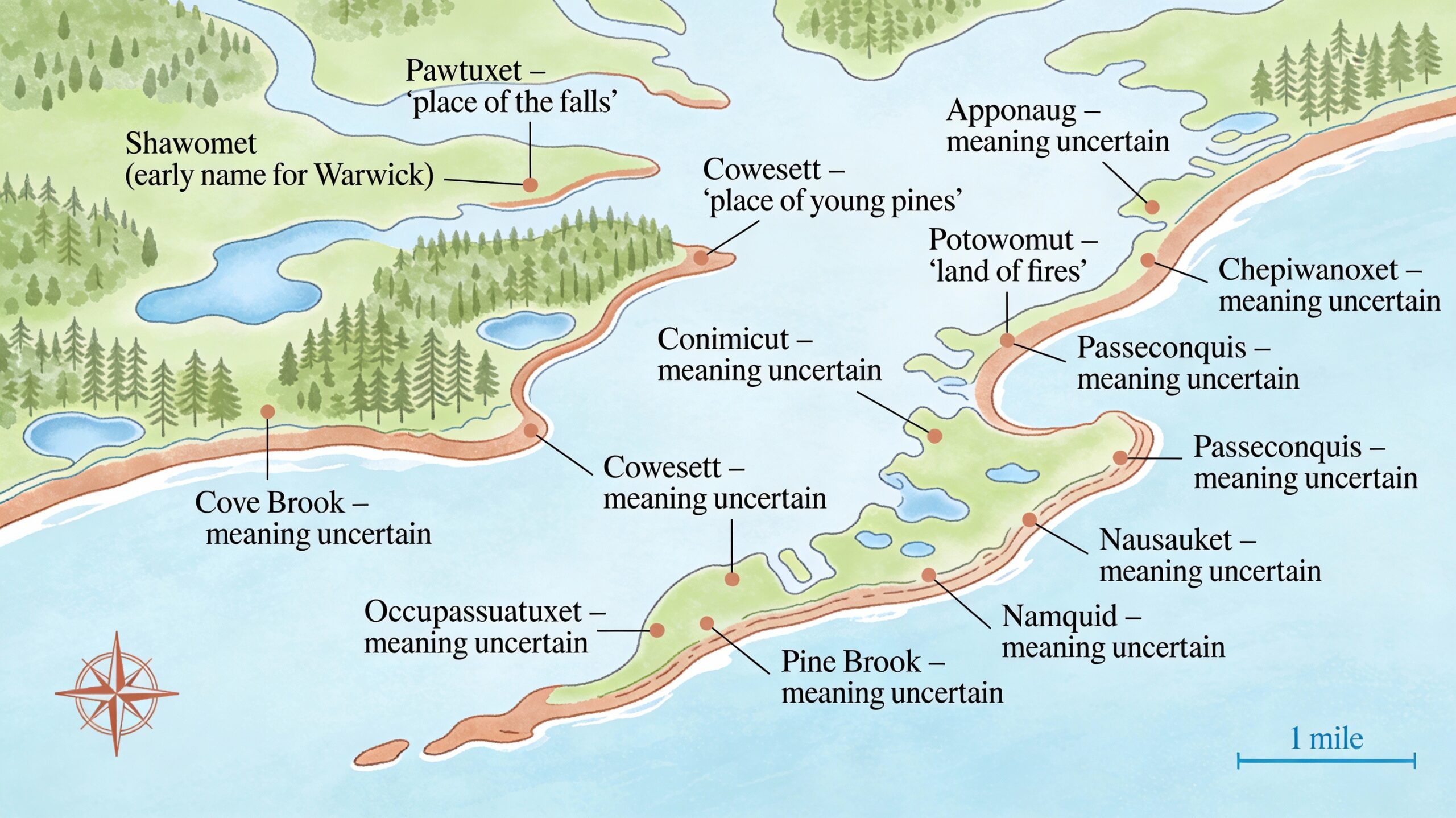

- Narragansett Stewardship: Before colonial settlement, the region was the heartland of the Narragansett people, known for sophisticated land management, sustainable agriculture, fishery, and forest stewardship, deeply integrated with their cultural and spiritual identity.

- Colonial Negotiations and Conflict: Land transactions were shaped by complex negotiations, with differing perspectives between Native American communal use and English individualized tenure—leading to long-term legal, cultural, and territorial consequences, as well as contested claims among neighboring colonies.

- Key Players and Events: Leaders like Miantonomi (Narragansett chief sachem) and influential settlers such as Samuel Gorton and Robert Westcott played pivotal roles in the critical land transfers and expansion of Warwick, especially in the flashpoint years of 1642 and 1659.

- Legacy and Consequences: The formalization of land claims through deeds contributed to rapid colonial growth, but also produced lasting impacts in terms of economic development, legal disputes, and cultural transformation—shaping Warwick’s fate and its place in Rhode Island history.

Cheesechamut’s Deed to Warwick Neck, Rhode Island stands as a remarkable testament to Warwick’s colonial history and its complex negotiations with local Native leaders. This historic document, preserved in the Yale Indian Papers Project, captures the 17th-century transfer of land between Cheesechamut, a Native American leader, and English settlers. Through original signatures, hand-written texts, and careful witnessing, the deed illustrates an era shaped by cooperation, change, and cultural crossroads. Examining this image offers insight into Warwick’s founding, the legacy of indigenous land stewardship, and the town’s unique story embedded in its earliest official records.

Cohost 1: Every major city, you know, every town has what you could call a foundational blueprint.

Cohost 2: Mhm.

Cohost 1: But that blueprint isn’t just about uh modern infrastructure or zoning laws. It’s about history.

Cohost 2: Right.

Cohost 1: It’s etched in ink, often tucked away in these fragile archives and, you know, ancient legal ledgers, and it details the story of the land itself.

Cohost 2: Who held it? Who negotiated for it?

Cohost 1: Exactly. And what the true cost of that transfer was.

Cohost 2: Yeah.

Cohost 1: Welcome to the Deep Dive.

Cohost 1: Today, we are taking you far beyond modern city planning, straight back to the 17th century heart of Rhode Island.

Cohost 2: And specifically, we’re focusing on Warwick.

Cohost 1: Yes, Warwick.

Cohost 2: Yeah.

Cohost 1: Our subject today is the dense, complicated, and uh utterly critical Indian land deeds that literally shaped its geography, dictated its economy, and really defined its fate.

Cohost 2: It’s a fascinating story.

Cohost 1: It is. So, our mission today is a deep intellectual dive, tailored for you, the learner. We’re going to act as expert navigators through some pretty dense historical documentation.

Cohost 2: And these are not simple summaries we’re working with.

Cohost 1: No, not at all. Our goal is to extract the critical nuggets from 17th century town records, from historical analyses, just to fully understand the intricate negotiations.

Cohost 2: And the motivations behind them.

Cohost 1: The dual motivations, and of course, the devastating consequences of these transactions.

Cohost 2: Mhm.

Cohost 1: We want to move past this, you know, simple abstract idea of settlement and really grasp the realities of the early colonial period.

Cohost 2: And the materials we have, they really let us do that. As you said, we’re not dealing with high-level summaries. We’ve gathered detailed analyses of original deeds, historical town records.

Cohost 1: The real stuff.

Cohost 2: The real stuff, and interpretive essays on early colonial history. This granularity is, well, it’s essential. It gives us this village-level, almost day-by-day view of agreements that were hammered out face-to-face.

Cohost 1: Which lets us analyze the long-term legal and cultural implications.

Cohost 2: Exactly.

Cohost 1: But before we rush into the names and dates of 1659, which is really the flashpoint year here, we have a critical requirement.

Cohost 2: We have to set the stage.

Cohost 1: We have to set the physical and spiritual stage. If we don’t understand the landscape and, more importantly, its original caretakers, then the deeds themselves, they just become meaningless scraps of paper, completely divorced from human experience.

Cohost 2: That’s exactly right. The legal transfers we’re about to analyze only gain their true significance when they’re placed against the backdrop of what was actually being transferred.

Cohost 1: Okay, so let’s unpack this context thoroughly. When the early English settlers first arrived in the area that would eventually be named Warwick, what they saw was, well, in their view, it was potential.

Cohost 2: Right.

Cohost 2: Land to be claimed, developed.

Cohost 1: To be put to use under a new system. But the reality on the ground was far different. What was truly there?

Cohost 2: What was truly there was an ancient, sophisticated human landscape. I mean, for thousands of years before any European arrival, this region was the home and the heartland of thriving Native American communities.

Cohost 1: We’re talking specifically about the Narragansett people here.

Cohost 2: Specifically the Narragansett people, yes. They were the primary original inhabitants of this territory. Their influence extended across much of what is now modern-day Rhode Island and even into parts of Connecticut.

Cohost 1: And when historians and archaeologists describe their relationship with the land, it sounds like it’s far beyond just, you know, inhabiting it.

Cohost 2: Oh, absolutely. It suggests a really sustained, integrated relationship.

Cohost 1: Can you tell us more about the specifics of that land stewardship?

Cohost 2: Well, their system was one of profound integration. They farmed the productive soils, and they often used really sophisticated methods of crop rotation.

Cohost 1: Like companion planting.

Cohost 2: Exactly, like the famous three sisters, corn, beans, and squash, all planted together. This wasn’t transient agriculture. It was fixed, and it was foundational to their society.

Cohost 1: Okay.

Cohost 2: They also utilized the abundant natural resources. They were fishing the rich Narragansett Bay for shellfish and finned fish, and they were carefully managing the forests.

Cohost 1: Managing them how?

Cohost 2: Through things like controlled burns. This was a technique to encourage game to flourish in certain areas and also to maintain clear travel paths.

Cohost 1: So, their entire livelihood, their social structure, their food security, their spiritual health, it was all completely integrated into that specific physical landscape.

Cohost 2: The bays, the rivers, the forests, all of it.

Cohost 1: Which means their concept of land use and stewardship wasn’t just economic, it was fundamental to their very identity.

Cohost 2: That’s the crucial distinction. Archaeological evidence, the few remaining documented oral traditions, they all highlight a system of sophisticated land management that involved careful resource allocation and uh sustainable practices.

Cohost 1: And the European perspective was so different.

Cohost 2: Completely. The European perspective often described the land as wilderness, which implied it was untouched, unused.

Cohost 1: Wild.

Cohost 2: Wild. But the Narragansett reality was precisely the opposite. It was a landscape of careful cultivation, managed down to the smallest detail.

Cohost 1: This inherent sophistication really sets up the later conflicts perfectly.

Cohost 2: It does.

Cohost 1: When you have two entirely different legal and spiritual frameworks, one built on this idea of permanent individualized tenure, the other on communal use and a spiritual connection, when they collide over the same piece of ground, well, profound misunderstandings and exploitation seem almost inevitable.

Cohost 2: And that leads us to the first critical legal step. It’s one that often gets overlooked because it precedes the 1659 surge, but it provides the um the legal hook for the settlers.

Cohost 1: The Miantonomi deed of 1642.

Cohost 2: Exactly. This is that first stone in the path we mentioned, but let’s dive into its content. Who was Miantonomi, and what did that 1642 transaction specifically involve? Why was it so foundational for Warwick?

Cohost 2: So, Miantonomi was a powerful and pivotal leader. He was the chief sachem of the Narragansett.

Cohost 1: A top leader.

Cohost 2: Yes, and he was navigating a really volatile political climate. He was balancing pressures from rival native groups like the Mohegan, and also the aggressive expansion of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Cohost 1: A tough position to be in.

Cohost 2: Very tough position. The 1642 deed was part of what became known as the Shawomet Purchase.

Cohost 1: Okay, the Shawomet Purchase.

Cohost 2: In 1642, Miantonomi deeded a massive tract of land, what would become Warwick, to a, well, a pretty controversial English settler named Samuel Gorton and his associates.

Cohost 1: And the agreement was specific?

Cohost 2: It was. It conveyed the title to the settlers, establishing the initial legal framework that Warwick would later rely upon for all its territorial claims. This purchase gave the settlers the necessary legal documentation, in English form, to assert ownership.

Cohost 1: Even though the sale itself was contested?

Cohost 2: Deeply contested, especially by other colonial neighbors like Massachusetts, who had their own ambitions for that land.

Cohost 1: So, Gorton and his group, they had the paper. They had the deed signed by a major sachem, Miantonomi. But the actual viability of their claim was still highly disputed by other English colonies.

Cohost 2: That’s it in a nutshell. The foundation was legally shaky, but it existed.

Cohost 1: It’s a contested claim, but it is a formal claim. It’s documented under English law.

Cohost 2: And that’s the key. That 1642 transaction created the magnet that drew more settlers and fueled the later much larger expansions. It essentially signaled to others, this land is now open for formalized English settlement.

Cohost 1: And this context, it sets the stage perfectly for the dramatic acceleration that occurred 17 years later.

Cohost 2: Yes.

Cohost 1: So, we move from this ancient, highly organized Narragansett presence, through this contested but foundational legal step taken in 1642, and we arrive at the true flashpoint of expansion. The mid-17th century.

Cohost 2: We’re now turning the calendar to 1659.

Cohost 1: The year the destiny of Warwick was truly sealed.

Cohost 2: Yeah.

Cohost 1: All right, so here’s where our analysis of the actual documentation begins. 1659 is the year that those claims made back in 1642 really became solidified.

Cohost 2: Right.

Cohost 1: It’s where a contested claim transforms into a rapidly expanding permanent settlement through the formal transfer of these massive tracts of land.

Cohost 2: In that year, the pressure just reached a critical mass. The colonial population was increasing so rapidly, and the demand for legally recognized permanent holdings was immense.

Cohost 1: So, the Narragansett leaders, who had already made the calculation back in ’42 that accommodation might be necessary for survival, now they were attempting to manage a relentless tide of newcomers.

Cohost 2: Let’s start with the first major transaction we’ve identified from that pivotal year. We have the specific date, the deed to Robert Westcott, June 23, 1659. What do the records tell us about this specific land transfer and the settler involved?

Cohost 2: This was a cornerstone event. Local native leaders formally deeded significant tracts of land to this Robert Westcott.

Cohost 1: And who was he? Just a typical settler?

Cohost 2: No, far from it. Westcott was noted in the town records as an influential and wealthy proprietor. He had the capital and uh the political connections to leverage large-scale acquisitions.

Cohost 1: So, he was a major player.

Cohost 2: A very major player. The documents indicate that Westcott received these substantial tracts of land that were crucial for Warwick’s immediate expansion, both along the coastline and for the inland farming areas.

Cohost 1: So, it was a strategic acquisition.

Cohost 2: Extremely strategic. It provided the space necessary for building mills, for establishing larger farms, and for attracting further colonial investment. It was about growth.

Cohost 1: And when we look at the documentation, we see that colonial priority, rigidity and formality. They needed that official 17th century legal structure.

Cohost 2: Absolutely. The settlers were meticulous about documenting these transfers. This transaction is preserved in original 17th century ledgers and town records.