What’s your opinion of the Roundabouts in Warwick? As a new resident I’m impressed by them and love not having to stop at a traffic signal. What I didn’t know is how much of a change the project of converting a dysfunctional traffic pattern in the city set an example for the entire state. This is a longer podcast (transcription below for you that would rather read) but it tells the story of this change and how impactful it has been.

Here are the 5 main takeaways:

Apponaug’s Traffic Crisis: Warwick’s historic center, Apponaug, was plagued by a badly designed, decades-old one-way circulation system that caused chronic gridlock, dangerous conditions, and economic decline. Regional connectivity was strong, but local circulation was broken, threatening downtown viability.- Transformative Project & Design: The nearly $71 million Apponaug Circulator Improvements Project built a new bypass and converted five major intersections to modern roundabouts. This radical infrastructure overhaul prioritized both efficient traffic flow and safety, setting a statewide example.

- Economic, Safety, & Livability Impact: The project delivered a 73% reduction in traffic volume through the village center, unlocked revitalization and business investment, and made the area safer. Crash statistics point to a 35% overall reduction, with even higher decreases in severe and fatal crashes (up to 76-100%).

- Environmental Restoration: Major improvements included daylighting and restoring the Apponaug River, upgrading flood protection and stormwater treatment, and reconnecting natural features with the community, alongside cleaner air and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

- Statewide Policy Legacy: The project’s success shifted Rhode Island’s approach to transportation safety and funding, leading to data-driven, systemic safety programs and accelerated installation of effective countermeasures statewide. Its benefit-cost ratio of 4.4 proved the investment paid off dramatically, and the template continues to shape future projects.

Cohost 1: I want you to imagine a critical congestion problem in your town. The traffic is just, it’s soul crushing, the pollution is constant, and that historic downtown area feels less like a place for people and, you know, more like a high-speed concrete canyon where you’re kind of risking your life to cross the street.

Cohost 2: Mhm.

Cohost 1: Now, if you’re a transportation planner, what’s your traditional sort of knee-jerk solution?

Cohost 2: Well, for decades, that solution was pretty simple. Maximize throughput, bigger roads, wider lanes, fewer stops, just move cars faster. That was the classic engineering mandate.

Cohost 1: Right.

Cohost 2: But as the stack of sources we’ve got for this deep dive shows, fixing traffic congestion today doesn’t have to be just about moving cars. It can be, and in this case, it absolutely was, a full-fledged blueprint for, well, for profound urban renewal, community revitalization, and some massive environmental restoration.

Cohost 1: That intersection of engineering, economics, and ecology is exactly what we’re digging into today. Our mission is to really explore the Apponaug Circulator Long-Term Improvements Project in Warwick, Rhode Island. This thing was a colossal infrastructure overhaul. We’re talking a nearly $71 million wager on the power of modern roundabouts to pull a blighted urban core back from the brink.

Cohost 2: And we’re going to unpack in detail how those technical transportation criteria, you know, safety, efficiency, pure economics, were aligned perfectly with these much broader quality of life goals, things like livability and long-term environmental sustainability.

Cohost 1: Okay, so to guide us, what are we looking at? What are our sources?

Cohost 2: We have a really fascinating collection of official documents. We’re going to be examining the Rhode Island Department of Transportation’s, or RIDOT’s, original TIGER grant application from 2013.

Cohost 1: Ooh.

Cohost 2: That’s really the foundational document that lays out the ambition. But we also have subsequent project updates, financial reports, and some really extensive safety performance analyses. I mean, these sources lay out the whole story, the complex genesis, the very complicated financing, and the definitive systemic outcomes of what was, for New England, a truly pioneering project.

Cohost 1: And here is the essential nugget to frame this whole conversation for you. Warwick, Rhode Island is the second most populous city in the state. And yet, the very heart of its historic core, the Apponaug business district, had fallen into such severe decline that the Federal Highway Administration, the FHWA, had officially flagged it as economically distressed.

Cohost 2: Right. This wasn’t just fixing a road. This was a high-stakes, decades-in-the-making attempt to reverse that decline, using civil engineering and specifically modern circulation design as the catalyst.

Cohost 1: So, let’s start there. Let’s dig into that blighted center and really understand the crisis in Apponaug.

Cohost 2: To really get the scale of this, you first have to understand the context of Warwick itself. The community is right in the middle of the critical Northeast corridor of the US. And in the period leading up to this, you know, the early 2010s, the region was really grappling with some chronic challenges. Stagnant economic growth, for one, and a persistent high unemployment rate.

Cohost 1: And the sources have specific numbers on that, right? It paints a picture of real hardship.

Cohost 2: They do. In 2012, Warwick’s average unemployment rate was 9.4%.

Cohost 1: Wow, 9.4%. That’s significantly higher than the national average at the time.

Cohost 2: Oh, absolutely. And that number, combined with other conditions across Kent and Providence counties, is what led directly to that official economically distressed designation from the FHWA.

Cohost 1: And that designation, that’s more than just a label, right? It actually unlocks things.

Cohost 2: It’s critical. It empowered state planners, like RIDOT, to formally recognize that the road problems, the chaos on their streets, weren’t just an inconvenience. They were actively, measurably limiting any potential for local economic recovery.

Cohost 1: Which is so counterintuitive when you look at the region’s assets. I mean, Warwick should be a major transportation hub. It’s got TF Green Airport, a major commercial airport for the whole region.

Cohost 2: It does. You’ve also got the InterLink commuter rail station right there, connecting the city regionally, and it has fantastic proximity to I-95 and 295.

Cohost 1: So, the regional connectivity was great. The problem was local. The circulation was just broken.

Cohost 2: That’s the key distinction. Regionally, Warwick was connected, but locally, the heart of the city, Apponaug Village, was basically dying because its own road network was so fractured.

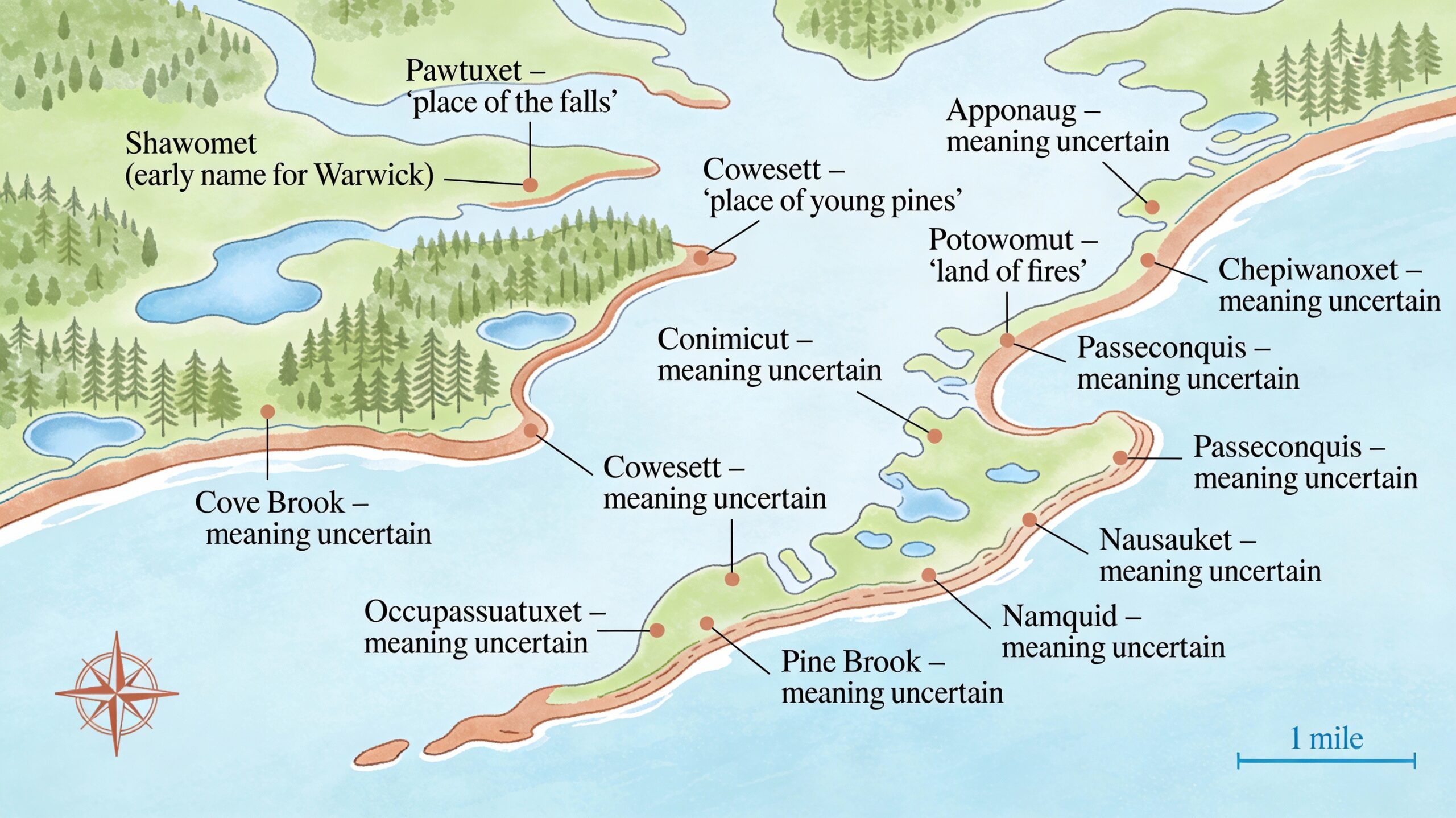

Cohost 1: And this place has deep historical roots.

Cohost 2: Very deep. It was settled back in 1696. It grew up as a civic and cultural center, you know, powered by the Apponaug River’s hydropower. Warwick City Hall is right there. It is, by definition, the government center. And yet, decades of really poorly planned circulation had just choked the life out of it.

Cohost 1: Okay, let’s unpack that physical chaos. We’re talking about this, this outmoded circulator system. What’s so fascinating, and frankly frustrating, is that this mess wasn’t an accident. It was engineered back in the ’70s.

Cohost 2: It was.

Cohost 1: And it was supposed to be temporary.

Cohost 2: That’s the key. A temporary measure that, through just decades of bureaucratic inertia, became permanent for nearly 50 years.

Cohost 1: Unbelievable. What was it exactly?

Cohost 2: It was a highly inefficient four-leg, one-way traffic circulation system.

Cohost 1: Yeah.

Cohost 2: And these roadways included critical arteries that should have been supporting local businesses, Post Road, which is US Route 1, and State Route 117.

Cohost 1: Okay.

Cohost 2: And crucially, they were classified by the state as urban principal arterial highways. Now, that classification is reserved for roads designed to move the highest volumes of traffic as fast as possible through an area, often prioritizing regional transit way over local access or pedestrian safety.

Cohost 1: And that staggering through-traffic volume was the problem. The sources say the eastbound leg, Post Road, was carrying an estimated 24,500 vehicles a day.

Cohost 2: Per day.

Cohost 1: Directly through the historic business district and right in front of City Hall. That’s an astonishing amount of traffic for a village center.

Cohost 2: It basically turned the historic district into an ad hoc, high-speed regional bypass. It was everything a vibrant town center was designed not to be. And the city officials were crystal clear in their assessment. That massive, unmitigated through-traffic was the singular primary cause for the social and economic decline of Apponaug.

Cohost 1: It’s the noise, the pollution.

Cohost 2: Exactly. The incessant loud noise, the air pollution, the severe congestion, and most critically, it created these constant, frankly frightening conflicts between fast-moving cars and any person trying to walk or bike in the area. The existing pattern was actively discouraging new investment.

Cohost 1: So, beyond the socioeconomics, the engineering itself was just failing. What were the specific geometric problems that RIDOT pointed to?

Cohost 2: Oh, the list in the TIGER application was exhaustive. It detailed these chronic failures of standard design practice. For instance, the existing lane widths were only 10 ft wide.

Cohost 1: 10 ft. Now, that sounds, I mean, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, or AASHTO, they recommend 11 ft, right?

Cohost 2: A minimum of 11 ft for a road of that classification.

Cohost 1: So, hold on. A difference of 1 ft, that sounds really minor to a layperson. Why is that extra foot so critical?

Cohost 2: That extra foot is your entire margin of error. 10 ft lanes feel incredibly restrictive, especially with the heavy truck traffic you get on US Route 1. It forces trucks unnervingly close to the curb, or if a car drifts just a little, they’re close to the center line. That standard 11 ft width, it just reduces vehicle wander, it provides a critical buffer in wet or icy conditions, and it psychologically signals to drivers that the road is designed for comfortable, predictable travel.

Cohost 1: Not for just squeezing through.

Cohost 2: Exactly. And in Apponaug, this constant lack of margin just amplified driver stress and, of course, reduced overall safety.

Cohost 1: What else was wrong with the design?

Cohost 2: Well, they cited narrow or totally non-existent shoulders. There were five specific horizontal curves, bends in the road, that didn’t meet the AASHTO minimum design criteria for the speed limit.

Cohost 1: Meaning they were just dangerous.

Cohost 2: Potentially, yes. There was poor curb reveal, which means drivers couldn’t easily tell a side street from a simple driveway, creating confusion. And critically, you had these severe weaving conflicts, where drivers had to quickly switch lanes to get where they were going inside this one-way loop.

Cohost 1: And all of that led to a level of service F during peak hours. Break that down for us. What does LOS F actually feel like for a commuter?

Cohost 2: Right. So, transportation engineers grade traffic flow from A to F. A is free flow, open highway. F is the absolute worst. It’s defined as forced flow.

Cohost 1: Forced flow.

Cohost 2: That means the number of cars on the road exceeds the road’s maximum capacity. For commuters, that’s just severe chronic gridlock. It’s bumper to bumper, where your speed is dictated entirely by the car in front of you. It’s a road system that is completely broken down.

Cohost 1: So, a total operational and safety catastrophe. And what’s just remarkable is how long this problem sat unsolved. The first real push to fix this was a study way back in 1986.

Cohost 2: 1986.

Cohost 1: Almost three decades before they even broke ground. That timeline is key to understanding the political will that built up later.

Cohost 2: Right.

Cohost 1: Back in ’86, a study looked at alternatives. Initially, they prioritized short-term fixes, you know, the usual Band-Aid approach. But here’s where the local leadership showed some real vision. In 1993, the city of Warwick formally asked RIDOT to postpone any reconstruction indefinitely.

Cohost 2: They asked them to stop.

Cohost 1: They did, to focus instead on a comprehensive long-term bypass that would actually align with their revitalization goals. They realized that just spending money to smooth out the existing mess would be counterproductive. It would just make the decline of the city center more efficient. They demanded a complete paradigm shift.

Cohost 2: And that set the stage for the preferred alternative they finally landed on years later, building a brand new two-way bypass system to route all that regional traffic around the historic core.

Cohost 1: That bypass was the logistical release valve. The core new segment involved extending a road called Veterans Memorial Drive, and this required building a new road that literally cut through the footprint of a disused old mill complex to connect to the junction of Toll Gate Road and Centerville Road.

Cohost 2: So, by building this new route, by building this new route, the whole idea was to relieve the historic Main Street, Post Road, of its terrible burden as a principal arterial highway. That would finally allow the city to implement those long-range redevelopment plans they’d been pushing for since the early ’90s.

Cohost 1: And here is where the design choice becomes radical. Here is where the $71 million bet really comes in. The initial bypass concept, that was approved way back in 2005. But between then and the actual grant application, they made a key refinement. They decided to replace the traditional signalized intersections with something pretty uncommon for America at the time, modern roundabouts.

Cohost 2: That shift was a massive policy statement for Rhode Island. They decided to convert five major nodes, including the infamously congested Apponaug Four Corners, into modern roundabouts. This wasn’t a minor tweak. This was leveraging state-of-the-art 21st-century urban design, driven by a need to handle the traffic on the new bypass, but also, critically, to enhance safety and enforce lower speeds.

Cohost 1: It’s still often a hard sell to the American driver, though. You hear the complaints all the time. They’re confusing, or they slow things down. But the safety data is just overwhelmingly clear. Let’s really focus on the hard numbers that justified this.

Cohost 2: The statistics cited in the grant application, they are undeniably dramatic. Based on studies from all over the country, they consistently showed that these conversions result in an overall 35% reduction in total crashes.

Cohost 1: 35% is substantial for any traffic planner, but the reduction in crash severity, that’s the real headline here. This is the difference between a fender bender and a life-altering event.

Cohost 2: Absolutely. The impact on injury severity just fundamentally changes the risk for the community. The data shows a staggering 76% reduction in injury crashes.

Cohost 1: 76%.

Cohost 2: 76. And if you look at the most devastating collisions, the fatal and incapacitating injury crashes, the figures were estimated at about a 90% reduction. Our sources even quote one national study that reported a 100% reduction in fatalities.

Cohost 1: 100%. I mean, if you’re an engineer planning for public safety, those are morally compelling numbers. They have to outweigh any inconvenience of learning a new traffic pattern. So, mechanically, how do roundabouts do that? How do they achieve such dramatic safety improvements?

Cohost 2: It’s a combination of physics and human psychology. First, they eliminate the most high-severity conflicts. At a normal four-way intersection, you have cars crossing directly through the path of oncoming traffic. That leads to high-speed T-bone and head-on crashes.

Cohost 1: The most dangerous kind.

Cohost 2: The most dangerous. A roundabout forces all turning movements to happen at angles. It converts those potential T-bone crashes into glancing, low-speed side-swipe conflicts. The speed is low, the angle of impact is low, so far less energy is transferred in the collision.

Cohost 1: But the speed is key, right? The design itself forces you to slow down.

Cohost 2: Precisely. The second critical function is forcing a lower speed profile. And the Apponaug design included some specific engineering to achieve this. For example, they carefully landscaped the central islands. This wasn’t just for decoration.

Cohost 1: It’s a functional barrier.

Cohost 2: Highly functional barrier. It prevents drivers from engaging in what we call sight-reading the intersection. If the central island is clear, a driver approaches at high speed, sees a gap on the other side, and they try to just shoot through.

Cohost 1: Right.

Cohost 2: But by putting landscaping, trees, big architectural elements in the center, you block that long sight line. That simple act forces the driver, instinctively, to slow down as they enter and circulate, because they can’t predict what’s coming next.

Cohost 1: That’s fascinating. And this was critical for Apponaug because four of the major intersections in the area already had accident rates higher than the acceptable threshold.

Cohost 2: Much higher than the ITE, the Institute of Transportation Engineers, benchmark of 1.5 crashes per million entering vehicles. So, the roundabouts were really a surgical solution to these known high-risk zones.

Cohost 1: So, once they locked in that traffic mechanism, the bypass to siphon the through-traffic and the roundabouts to manage local flow, the real project of livability and economic vision could finally begin. The sources call the bypass the linchpin for the entire economic revitalization. That’s a powerful claim for a road project.

Cohost 2: It really speaks to the holistic strategy. The city knew that just building a better road somewhere else wouldn’t magically bring people and businesses back. They needed regulatory changes to support it. So, in anticipation of the new lower traffic volumes, Warwick instituted a new village district zoning designation for Apponaug.

Cohost 1: And that was a crucial change.

Cohost 2: Crucial. The new code acknowledged the unique historic character of the village and provided the flexibility needed to foster mixed-use development, encourage live-work opportunities, and just generally grant more flexibility for businesses.

Cohost 1: And the change to Post Road, that old highway that had been the clogged heart of the village, that was immediate and transformative. It went from 24,500 vehicles a day down to a projected 5,000. That massive drop allowed them to execute what’s known as the road diet.

Cohost 2: And that road diet was fundamental. Before, the road was all about moving cars, two travel lanes, two parking lanes. The new configuration completely redefined the street’s purpose. It became one single travel lane in each direction, two dedicated parking lanes, and a dedicated bicycle lane.

Cohost 1: That completely shifts the street’s priority, doesn’t it? It goes from moving cars through the community to serving people in the community.

Cohost 2: The psychological impact is profound. Four lanes screams speed and efficiency. Reducing the lanes forces drivers to slow down, be more aware of their surroundings, and when you add dedicated parking and bike lanes, you create a buffer between the moving cars and the people on the sidewalk.

Cohost 1: Which makes people feel safer.

Cohost 2: It creates perceived and actual safety, encouraging people to walk, to sit, to linger.

Cohost 1: And speaking of people, what about the pedestrian and cycling experience? The sources say that was pretty much non-existent before because of the traffic.

Cohost 2: They did a complete overhaul of the streetscape, focusing on human scale. The improvements were comprehensive and, crucially, had to be fully ADA compliant, so widened, accessible sidewalks. They used visually distinctive colored concrete for crosswalks to increase visibility.

Cohost 1: And they used curb bump-outs. Explain what those are for.

Cohost 2: Curb bump-outs are ingenious traffic-calming devices. They jut out into the street at intersections. Their main job is to significantly shorten the crosswalk.

Cohost 1: Ah, so pedestrians are exposed for less time.

Cohost 2: Exactly. They also visually narrow the street, which forces drivers to slow down, and they improve sight lines between drivers and pedestrians. You couple that with period-appropriate lighting, extensive landscaping, and you get traffic calming throughout the whole district.

Cohost 1: And this ambition wasn’t just limited to the village itself. The long-term plan was to connect this new pedestrian-friendly place to the wider regional transit system.

Cohost 2: That’s right. The city made it a priority to connect Apponaug, with these new bike and pedestrian facilities, directly to the InterLink multimodal station at TF Green Airport. They were even looking at extending the road diet concept to nearby Jefferson Boulevard to create continuous bike lanes. It’s all part of a larger shift toward transit-oriented development.

Cohost 1: Moving beyond just traffic and commerce, the project even impacted how the city runs its own government, creating this idea of a new civic center.

Cohost 2: It’s a fascinating side benefit. As part of the land acquisition for the bypass, RIDOT acquired a historic mill building right near City Hall. This allowed the city to consolidate government offices that were scattered across three different locations into a new, unified civic center.

Cohost 1: And that had real cost savings.

Cohost 2: It did. The consolidation was projected to save nearly $68,000 a year just in municipal staff travel time and costs. And beyond that, it improved public access to cultural things, like the Warwick Museum of Art, and restored access to natural features, like the Apponaug Cove shoreline, which had basically been walled off by traffic.

Cohost 1: Now, let’s pivot to the environmental sustainability component. This was maybe the single strongest argument they had for getting that competitive federal grant money. This was way more than paving roads.

Cohost 2: Oh, absolutely. This was fundamentally designed for long-term environmental restoration. It required extensive coordination with RIDEM, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the US Army Corps of Engineers.

Cohost 1: Let’s start with air quality. By reducing congestion, you reduce vehicle miles traveled and fuel consumption. What were the actual numbers on that?

Cohost 2: The modeling was robust. They projected carbon monoxide would decrease by 145 kg a day, nitrogen oxides by almost 7 kg a day. And critically, because you’re reducing idling, the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide was projected to decrease by over 2,900 kg per day.

Cohost 1: Wow.

Cohost 2: That quantification helped Rhode Island show it was serious about meeting national ambient air quality standards.

Cohost 1: But the truly impressive, transformative part of this whole thing, the most complex engineering feat, was about water resources and flood protection. The Apponaug River had been completely compromised by centuries of industrial use.

Cohost 2: That industrial legacy left the river functionally broken. The centerpiece of the environmental solution was a dramatic relocation and restoration of the Apponaug River. Engineers essentially daylighted the river. They moved it out from its old, broken culvert back into a brand new, naturalized channel that ran parallel to the new bypass road.

Cohost 1: Daylighting a river, that is a monumental effort.

Cohost 2: It is. And the restoration included enhancements for fish passage, specifically for alewife, a key migratory species, to get to their upstream spawning grounds.

Cohost 1: And the benefits extended to Hardy Pond, too, right?

Cohost 2: They did. Hardy Pond was basically a degraded wetland, another casualty of the old mill development. The project involved modifying old flow control structures to successfully restore the pond as a functioning water body and a sanctuary habitat.

Cohost 1: And this wasn’t just for looks. This had a real flood protection upgrade.

Cohost 2: A major upgrade. The new system is capable of safely conveying up to the 100-year flood event without surcharging the bridges. That means no water over the roadway, less risk to property. It was a major, necessary upgrade.

Cohost 1: And finally, it addressed water quality flowing into Greenwich Bay.

Cohost 2: Absolutely essential. Before this, the village’s outdated drainage just discharged untreated runoff directly into the bay, contributing to shellfishing and swimming closures. The project fixed this by building a new wet extended detention basin to manage runoff from 16 acres of impervious surface.

Cohost 1: So, it treats the stormwater before it gets to the bay.

Cohost 2: Exactly. It incorporates low-impact development and best management practices to dramatically reduce pollution. And we have to mention, the construction also required the careful management and removal of contaminated soils from the old mill complex, reducing long-term public health risks.

Cohost 1: Okay, so we have a project that’s economically vital, environmentally transformative, and technically groundbreaking. But projects this complex, especially in old industrial areas, they rarely come in on budget. Let’s dig into the financial architecture and cost reality.

Cohost 2: You’re right. The initial estimate back in the 2013 grant application was a substantial $33.5 million. And securing that required a careful blend of state prioritization and winning those highly competitive federal grants.

Cohost 1: They managed to stack the funding pretty well.

Cohost 2: They did. The federal government committed $26.8 million in total. That included the absolutely critical $10 million TIGER grant, plus money for the National Highway Performance Program and other federal funds. Rhode Island committed a $6.7 million state match.

Cohost 1: But as you said, the final reality was significantly higher. The final reported total project cost hit $71 million, more than double the initial projection. That is a massive jump. How did they justify that?

Cohost 2: That jump is absolutely where the public debate was focused. It’s crucial to understand that the initial $29.8 million construction contract covered the roadway elements. The remaining $41 million covered all the complex non-roadway stuff that you find in an old industrial environment.

Cohost 1: So, what drove that extra $40 million specifically?

Cohost 2: It was entirely driven by the unexpected complexity of the site conditions. Remember, we talked about the environmental parts, the full relocation of the river, remediating contaminated soils from the old mill, and the massive scale of utility relocation in a dense area.

Cohost 1: Things you can’t really know until you start digging.

Cohost 2: Exactly. These were requirements imposed by federal environmental agencies that you can’t fully quantify until you get on site. The justification was that these costs were unavoidable if they wanted to achieve the holistic goals that won them the TIGER grant in the first place.

Cohost 1: Despite that cost increase, the project showed remarkable project readiness and political will, which is often what gets a project noticed in DC.

Cohost 2: That political push was essential. RIDOT was ready to award the construction contract in 2013, even when they were facing a funding shortfall. They considered Apponaug such a high priority, they officially stated they would defer other state projects to make it happen.

Cohost 1: And there’s the great political anecdote here, the fact that this specific application won the TIGER grant over the proposal from the capital city, Providence.

Cohost 2: Yes. This is a critical point. Then-Governor Lincoln Chafee, who was actually a Warwick resident and a former mayor, famously supported the Apponaug application over Providence’s competing proposal for a much flashier $39 million streetcar line.

Cohost 1: Why did a complex congestion fix with roundabouts and a river restoration beat a big public transit project like a streetcar?

Cohost 2: The TIGER program was designed for projects with multimodal benefits, innovation, and national significance. The streetcar was just a transit project. The Apponaug Circulator was a true multi-benefit project. It wasn’t just roads. It was innovative safety with the roundabouts, economic revitalization with the zoning, environmental restoration with the river, and ADA compliance and bike-dot access. It checked every single box.

Cohost 1: So, it was just a more comprehensive proposal.

Cohost 2: A far more attractive, comprehensive use of those competitive federal funds. And having the governor’s support, prioritizing it over the capital city’s project, was the final proof of critical local and state buy-in.

Cohost 1: All this complexity means a long timeline, though. From that initial ’86 study to a 2005 design to construction starting in 2014 and finishing in 2017, it just highlights the immense challenge of these projects.

Cohost 2: It does. But the Apponaug success provided an even deeper legacy. It served as the foundation for a statewide shift in safety policy, specifically how RIDOT approaches funding through the Highway Safety Improvement Program, or HSIP.

Cohost 1: A key long-term legacy. Apponaug validated using predictive and systemic safety solutions. How did RIDOT shift its strategy for that HSIP funding?

Cohost 2: They pivoted radically. Previously, a lot of DOTs focused on what are called hotspot locations, you know, addressing the intersection where three fatal crashes just happened. The new strategy, validated by projects like this, is to focus 75% of HSIP funds on systemic programs.

Cohost 1: What’s the functional difference? Hotspot versus systemic?

Cohost 2: Hotspot funding is reactionary. It’s treating the symptom. Systemic funding is preventative. It treats the cause. Systemic programs target broad categories of high-risk roadway features across the entire state, whether or not a severe crash has happened there yet. The logic is, if a sharp, unmarked curve is known to cause crashes nationally, you systematically go out and fix all such curves across the state.

Cohost 1: And Apponaug also highlighted the frustration of waiting for these massive multi-year projects to deliver safety improvements.

Cohost 2: That’s right. The frustration of waiting three to four years for a fix. This led to a major policy innovation. In fiscal year 2023, RIDOT developed indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contracts, or IDIQ contracts.

Cohost 1: What do those do?

Cohost 2: They’re designed to streamline and accelerate the installation of proven safety improvements that don’t require major excavation, things like new signs, striping, flashing beacons for pedestrian crossings, high-friction surface treatments.

Cohost 1: How much faster are we talking?

Cohost 2: Dramatically faster. Instead of waiting three to four years, these IDIQ contracts let RIDOT deploy countermeasures to 40 or 50 locations a year, typically finishing the work in a much tighter 12 to 18 months.

Cohost 1: And they’re now developing their own state-specific data, crash modification factors, instead of just relying on national averages.

Cohost 2: Which is so valuable. Local conditions matter. For example, they found that their 17 installations of road diets showed a 29% reduction in all crashes and a 37% reduction in fatal and injury crashes. For high-friction surface treatments, they observed a staggering 73% reduction in wet pavement crashes. That proprietary local data feeds right back into their planning.

Cohost 1: Okay, finally, we have to confirm the financial success, the benefit-cost analysis, the BCA. Did the investment pay off?

Cohost 2: Overwhelmingly. The BCA is the financial justification for the whole thing. The present value of cumulative benefits, projected through 2040, was estimated at $175.4 million. That yielded a fantastic benefit-cost ratio of 4.4.

Cohost 1: So, for every dollar invested, the community sees $4.40 in return.

Cohost 2: That’s right.

Cohost 1: Where did most of that benefit come from? Because $175 million is a huge number.

Cohost 2: By far, the largest benefit came from travel time and reliability cost savings. That was $167.4 million. That’s the value of time saved by commuters, but also the crucial reliability savings for commercial businesses. When traffic is unpredictable, businesses lose money. When it’s reliable, even if it’s a bit slower, they save money.

Cohost 1: What about the other benefits?

Cohost 2: Vehicle operating cost savings accounted for another $7.4 million from less fuel and idling. The safety improvements, preventing those crashes, were valued at $434,000. And economically, the project supported 200 jobs at its peak and is expected to generate about 30 long-term jobs.

Cohost 1: Let’s transition to the key outcome then, the measurable impact now that the project is done. The goal was to redirect traffic away from the village center, and the success was dramatic.

Cohost 2: The results were undeniable. After completion in late 2017, the number of vehicles traveling through the historic village center on Post Road plummeted from 25,000 to just 6,800 vehicles per day.

Cohost 1: Wow. That’s a 73% redirection of traffic volume.

Cohost 2: A 73% redirection. The entire function of the historic district was instantly redefined.

Cohost 1: And that transformation, that immediate return of space and quiet, it served as an instant catalyst for investment, right? Do we have a concrete example of this?

Cohost 2: We do, and it’s a powerful one. The source specifically points to the 18th-century Sawtooth Building, which was part of that old mill complex. It had been isolated and blighted by the chaotic traffic. Post-project, with the road diet in effect, that building was sold, fully renovated, and became the modern regional offices of the American Automobile Association, AAA.

Cohost 1: Wait, hold on. The Automobile Association of America moved their offices into a newly roundabout-heavy, road-dieted, pedestrian-focused former construction zone.

Cohost 2: I know.

Cohost 1: That is the ultimate vote of corporate confidence.

Cohost 2: It’s the ultimate irony and proof of concept. The AAA moving into the heart of the new pedestrian-friendly Apponaug signaled renewed confidence and long-term investment. They recognized that the improved reliability, safety, and livability created a better environment for their own employees.

Cohost 1: So, the Apponaug project essentially gave Rhode Island a functional, data-driven template for how to handle complex urban infrastructure.

Cohost 2: It did. The success of Apponaug validated roundabouts, not as a novelty, but as a preferred solution for achieving both congestion relief and safety improvements at the same time. And we see this model being integrated into subsequent major capital projects across the state.

Cohost 1: Give us the specific examples that show this has been institutionalized.

Cohost 2: Okay, first is the Warwick Corridor project, a massive $102.4 million initiative. While its main job is replacing two bridges, the project now seamlessly integrates a new roundabout at a major intersection. This is a corridor with up to 33,000 vehicles a day. The fact that a roundabout is now a standard, non-controversial component shows how embedded this solution has become.

Cohost 1: And the second example shows its utility goes beyond just village centers.

Cohost 2: Precisely. The second is the I-95 Missing Move and Quonset Connector. This is a $135 million project designed to improve regional freight movement to the Quonset Business Park. It’s a strategic commercial logistics corridor. And yet, as part of this, a new roundabout is planned for Compass Circle. It proved they trust the operational capacity of the design even for high-volume logistics.

Cohost 1: And finally, that Apponaug success story gives the entire state DOT crucial leverage for future federal funding.

Cohost 2: Absolutely. Success breeds success in federal grants. RIDOT continues to build on the precedent set by the TIGER grant. They’re actively pursuing other grants, like an $81 million request for that Quonset freight project. Apponaug created a track record. It showed DC that Rhode Island could deliver exceptionally complex projects that expertly blend engineering, economic, and environmental goals.

Cohost 1: That is truly a remarkable story of urban infrastructure transformation. The Apponaug Circulator was never just about moving cars. It was a decades-long, comprehensive urban revitalization plan where success hinged on engineering traffic away from human activity. The entire $71 million strategy used hard data, that 4.4 BCA, the 76% crash reduction, to justify massive investment in livability and the environment. I mean, they daylighted a river.

Cohost 2: That’s the core learning here. The source materials clearly showed that this one project, completed in 2017, dramatically altered the public safety and economic development priorities for the entire state’s transportation department. It led to a decade-long systemic shift toward these advanced holistic solutions. It shows the power of challenging an outdated idea.

Cohost 1: So, for you the listener, we want to leave you with this final provocative thought. Think about your own community. What is the equivalent temporary or outdated transportation system in your local area? That clogged one-way street, that confusing