Here is your transcript with “[Unknown Speaker A]” replaced by Cohost 1 and “[Unknown Speaker B]” replaced by Cohost 2 throughout the entire text:

[Cohost 1] Welcome to the Deep Dive. Today we’re heading to Rhode Island, um, specifically diving into the story of Warwick. It’s a really complex history of changing boundaries and, well, revolutionary action.

[Cohost 2] It really is. We’re looking at how this place started, you know, with this initial big land deal, and then how pressures, political, geographical, caused it to expand, shrink, and even split apart over a couple of centuries.

[Cohost 1] Right. So our goal today, our mission if you like, is to unpack that foundational period, starting around 1642.

[Cohost 2] Exactly. We want to track how it went from essentially Native American land to these scattered farms, and then what happened next, right up through the early 20th century with some major historical markers.

[Cohost 1] And here’s something that really hooked me when I was looking into this. Warwick started out way bigger than it is now.

[Cohost 2] Much bigger.

[Cohost 1] But maybe even more importantly, it was the location of the, uh, the very first violent act against the British crown leading up to the revolution. That’s a huge claim to fame.

[Cohost 2] It’s a pivotal moment, absolutely.

[Cohost 2] And like you said, it all kicks off with this land transaction, basically engineered by its founder, Samuel Gorton back in 1642.

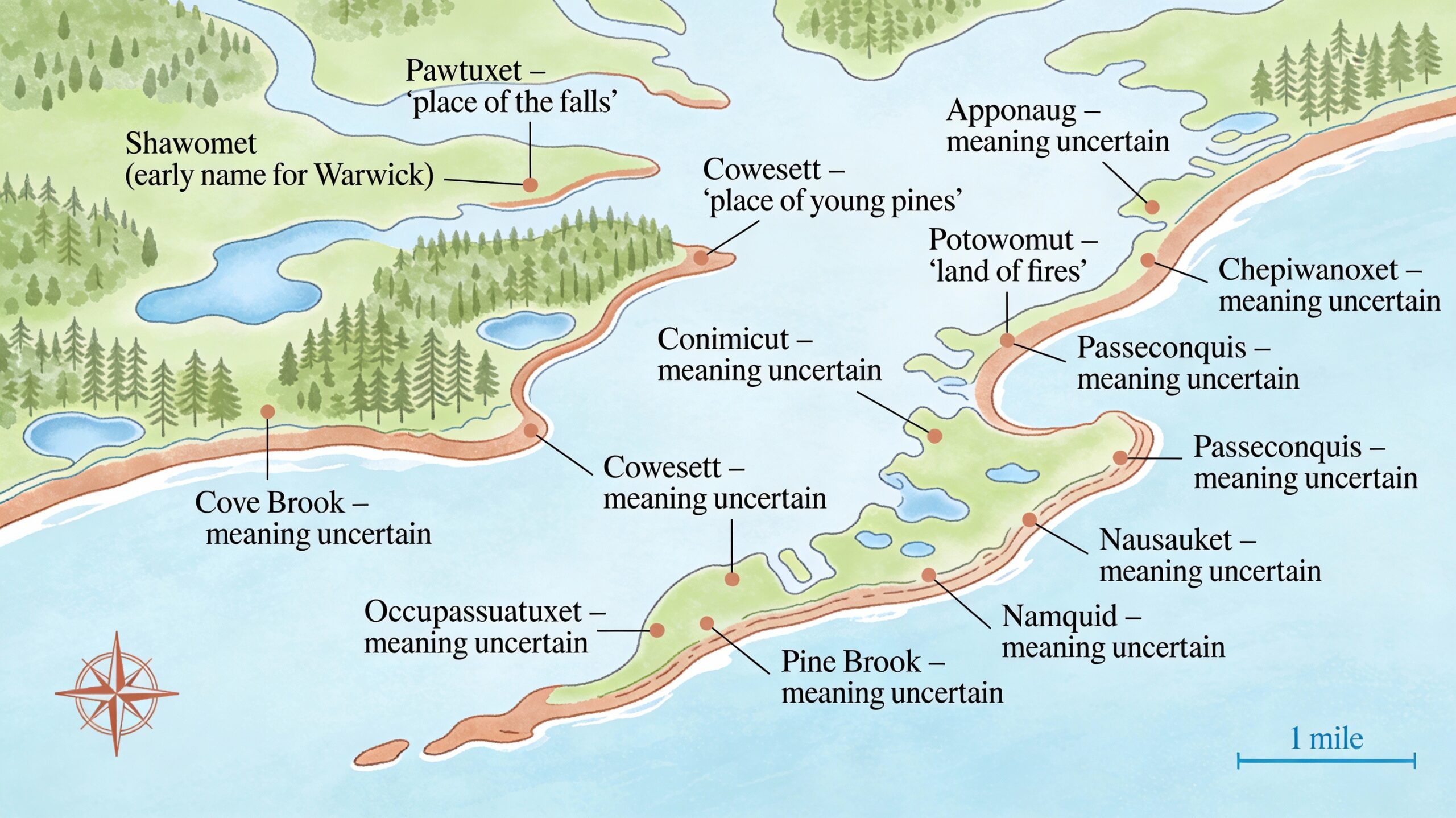

[Cohost 1] Okay, so let’s get into that. The Shawomet purchase. Gorton got this land from the Narragansett Sachem Miantonomi.

[Cohost 2] A major figure, Miantonomi.

[Cohost 2] And the land itself was vast. We’re not talking a small plot by the coast.

[Cohost 1] No.

[Cohost 2] The sources are clear. The original purchase included what we now know as Coventry and West Warwick. So the initial settlement was, well, enormous for colonial Rhode Island standards.

[Cohost 1] And the payment method, 144 fathoms of Wampumpeag. It sounds so specific. What are we actually talking about there?

[Cohost 2] Well, Wampum was the currency, mostly shell beads, you know, from quahog or whelk shells, carefully crafted.

[Cohost 1] Okay.

[Cohost 2] And a fathom here isn’t about depth, it’s length. Imagine a man’s outstretched arms measuring strings of these beads. So 144 fathoms was, uh, quite a substantial amount.

[Cohost 1] So it was a serious deal.

[Cohost 2] Definitely. It signifies a real negotiated purchase, not just taking the land, which is I think important for understanding how Warwick began as a trade.

[Cohost 1] Gorton gets the land, names it Shawomet, but that name doesn’t stick for long, does it? By 1648, it’s Warwick.

[Cohost 2] That’s right. And the name change was strategic. It offered political cover, really.

[Cohost 1] How so?

[Cohost 2] Gorton got a charter from Robert Rich, who’s the Earl of Warwick, very influential figure, the governor and chief for the colonies.

[Cohost 1] Ah, okay.

[Cohost 2] So naming the settlement Warwick linked it directly to this powerful English nobleman, giving it legitimacy and hopefully protection.

[Cohost 1] Makes sense. So you’ve got this huge area politically tied to England now, but what was day-to-day life like? What was the economy based on?

[Cohost 2] For a long, long time, maybe the first century, it was overwhelmingly agrarian. Just farming.

[Cohost 1] An agrarian hinterland, as the sources call it.

[Cohost 2] Exactly. This is the colonial architectural period right up to about 1775. You had scattered farms, people basically growing what they needed to survive, subsistence farming. They initially clustered near the bay in what did they call Old Warwick.

[Cohost 1] Right near the water.

[Cohost 2] Yeah. They weren’t really building big towns or ports yet. It was farming, raising animals, maybe cutting some timber further inland.

[Cohost 1] And that focus on the coast, you can already see the problem brewing, can’t you?

[Cohost 2] Oh, absolutely.

[Cohost 1] If everyone in power is by the bay, but your town technically stretches for miles west, governing that becomes a nightmare.

[Cohost 2] Precisely.

[Cohost 2] Which brings us to the next phase, this period of sort of fluid boundaries and the sheer problem of size. Even before the major splits, they were tweaking the borders.

[Cohost 1] Like adding the Potowomut Peninsula in 1654.

[Cohost 2] Yes. That was a specific purchase from Taximan. The reason, they needed more land for grazing livestock. It was practical.

[Cohost 1] Just practical needs driving expansion.

[Cohost 2] Right. And then later, 1696, the little settlement over in Pawtuxet gets officially added to Warwick. They were trying to make the boundaries match where people actually lived or where the resources were.

[Cohost 1] But that core issue, governing this massive spread out territory, it just wouldn’t go away.

[Cohost 2] No. And by the 1740s, the folks living way out west had basically had enough. Imagine riding your horse for miles and miles just to attend a town meeting or deal with town business.

[Cohost 1] It’s not sustainable.

[Cohost 2] Not at all. So you get the first big split in 1741. And what’s really interesting is the sources explicitly say why. Logistics.

[Cohost 1] Purely logistics.

[Cohost 2] The distance made communication with the eastern part, where the government was centered, so difficult that efficient government was nearly impossible. Their words. So they split off and formed the town of Coventry.

[Cohost 1] It raises a question though, if the problem was governing from the coast, why didn’t they just move the center of town government further inland, more central? Why did separation seem like the only answer?

[Cohost 2] That’s a great point. It probably boils down to colonial priorities and, well, power.

[Cohost 1] Ah.

[Cohost 2] The established families, the wealth, the political clout, it was all concentrated in Old Warwick near the bay. That’s where trade, even small scale happened. Moving the whole seat of government inland, that meant moving their power base, their records into what they probably still saw as the wilderness.

[Cohost 1] So it’s easier for the westerners to just leave.

[Cohost 2] Much easier for those folks out west, who likely felt pretty ignored anyway, to just cut ties and set up their own administration closer to where they lived. It’s a classic example of geographical inconvenience leading directly to political separation.

[Cohost 1] And solving that geographical problem administratively kind of paved the way for bigger organizational changes later on.

[Cohost 2] Definitely. Breaking up that original huge Warwick territory was a direct lead in to forming Kent County just a few years later in 1750.

[Cohost 1] Right, which included Warwick, Coventry, East Greenwich, West Greenwich.

[Cohost 2] Exactly. The fragmentation of that first purchase actually forced them to think about regional organization in a new way.

[Cohost 1] It almost sounds like once they learned they could solve problems by splitting things up administratively, they felt empowered to tackle, well, much bigger challenges.

[Cohost 2] Like challenging the king himself.

[Cohost 1] Which takes us right into 1772 and an event many historians point to as the real start of the American Revolution.

[Cohost 2] The Gaspee incident. Yeah, this might be Warwick’s single most significant contribution to American history. June 1772, local patriots row out, board the British revenue ship HMS Gaspee and burn it right down to the waterline.

[Cohost 1] And this is key. This happened three years before Lexington and Concord. So why is the Gaspee incident singled out as the first violent act against the crown?

[Cohost 2] It’s about the intentional violence against a representative of the king’s authority. The Gaspee was hated. It was aggressively enforcing unpopular trade laws, harassing local ships.

[Cohost 1] Right.

[Cohost 2] So when it conveniently ran aground near Warwick, a group, mostly from Providence and Warwick, saw their chance. They rode out. Lieutenant Dudingston, the commander, tried to resist.

[Cohost 1] I’m joking.

[Cohost 2] He got shot with a musket ball. That’s the first blood, English blood, spilled in an open act of defiance against the crown during this escalating conflict.

[Cohost 1] So it wasn’t just property destruction like the tea party later. This was direct violence against a British officer.

[Cohost 2] Precisely. And they were smart about it too. The sources mentioned they didn’t just burn the ship. First they stripped it of its cannons and weapons.

[Cohost 1] Neutralized it first.

[Cohost 2] Yes, took its military power away, then destroyed the evidence. And afterwards, when the crown launched this huge investigation, nobody in Rhode Island would talk, total stonewalling.

[Cohost 1] That coordination, that defiance, it really speaks volumes about the local attitude…

[Cohost 2] Fiercely independent. And that carried through the war. Warwick militiamen fought at Saratoga, Yorktown, key battles, but even after independence was won, Rhode Island kept that stubborn streak.

[Cohost 1] Oh yeah, the whole business with the Constitution.

[Cohost 2] Right. It’s a fantastic detail. Rhode Island initially refused to ratify the US Constitution. Voted against it.

[Cohost 1] Why the hold out?

[Cohost 2] They already had a strong bill of rights in their own state constitution. They felt the proposed federal one didn’t offer enough protection for individual liberties. They didn’t join the union until 1790.

[Cohost 1] Which must have caused some awkward moments for the new federal government.

[Cohost 2] You could say that. Yeah. Famously, when President George Washington traveled from New York to Boston early in his presidency, he had to go around Rhode Island.

[Cohost 2] Technically, yes, because until they ratified, Rhode Island considered itself an independent and sovereign republic. Imagine that George Washington, the hero of the revolution, having to bypass one of the original 13 colonies. It really underscores that fierce independent spirit.

[Cohost 1] Incredible. Okay, so moving into the 19th century, things change again dramatically. That agrarian background starts to fade.

[Cohost 2] And industry takes over. Driven by geography again, but this time it’s the asset of water power.

[Cohost 1] The rivers.

[Cohost 2] Especially the Pawtuxet River running through the interior. That abundant water power turned Warwick into a major center for textile manufacturing. Huge mills sprang up. It completely transformed the economy.

[Cohost 1] And one of America’s most famous brand names actually started right there, which shows the scale of this industrial boom.

[Cohost 2] That’s right. Fruit of the Loom, founded in Warwick at the BBNR Night Mill right on the Pawtuxet. That name itself tells a story from local farms to nationally recognized industrial products.

[Cohost 1] But this industrial wealth created a real divide, didn’t it? You had the mill owners and the workers clustered inland, while the coastline was attracting a completely different kind of wealth.

[Cohost 1] The millionaires.

[Cohost 2] Exactly. By the late 1800s, Warwick was known as one of the wealthiest places in the state. That beautiful 39 mile coastline, it became a magnet for America’s super rich. They built these enormous summer estates in areas like Conimicut, Warwick Neck, Buttonwoods.

[Cohost 1] I saw a note that for a time before the 38 hurricane and the depression hit, Warwick had more millionaires summering there than anywhere else in the country. Is that right?

[Cohost 2] That’s the claim. It’s astonishing, really. And it sets up this stark contrast. The industrial working class, densely populated west side around the mills, and the older agricultural, now incredibly wealthy and generally Republican east side along the coast.

[Cohost 1] That geographic and economic divide was practically begging for a political showdown.

[Cohost 2] Which finally happens in 1913, the creation of West Warwick. And unlike the Coventry split, this one wasn’t about logistics, this was pure politics.

[Cohost 1] Explain that.

[Cohost 2] Well, most of the town’s actual population and crucially its tax base was now concentrated around those textile mills on the west side of the Pawtuxet River.

[Cohost 1] Okay.

[Cohost 2] And those areas tended to lean democratic. So local democratic politicians saw an opportunity. They pushed for and succeeded in creating West Warwick. It was a calculated political move.

[Cohost 1] Calculated to do what specifically?

[Cohost 2] To secure their power, as the sources put it. By carving out their industrial democratic base into a separate town, West Warwick, they could basically guarantee political control over that whole economic engine. They effectively isolated it from the influence of the more Republican, agrarian, and wealthy eastern parts of Warwick.

[Cohost 1] Making West Warwick the newest town in the state at the time.

[Cohost 2] Yep. It’s a textbook example of how population shifts, driven by resources like water power, end up getting translated directly into political strategy and redrawing the map.

[Cohost 1] And Warwick itself, the remaining part, didn’t officially become a city until quite a bit later.

[Cohost 2] Not until 1931. They elected their first mayor, Pierce Burton in 1932.

[Cohost 1] So that really completes the arc, doesn’t it? From that huge unified Shawomet purchase in 1642, through two major splits, driven first by logistics and then by politics, to the reality we see today with Warwick and West Warwick existing side by side.

[Cohost 2] And it’s amazing, despite losing Coventry and then losing West Warwick, the city of Warwick itself is still the second largest city in Rhode Island today.

[Cohost 1] The whole story is just such a clear illustration of how the physical landscape, the coastline, the rivers, shapes where people live, and how where people live ultimately shapes political boundaries and even identities.

[Cohost 2] It really is. And it leaves you with a final thought to chew on maybe.

[Cohost 1] Okay.

[Cohost 2] Think about that first split in 1741, creating Coventry. It was driven by a simple, practical problem.

[Cohost 1] Yeah.

[Cohost 2] It was just too hard to communicate and govern across such a large distance back then.

[Cohost 1] Like the hassle of travel.

[Cohost 2] But that practical solution, splitting the town, set a precedent. It showed that division was possible. And then 172 years later, that same tool, division, was used again, but this time not for convenience, but for a deliberate political power play to create West Warwick.

[Cohost 1] Wow. So the difficulty of riding a horse in 1741 indirectly enabled a political maneuver in 1913.

[Cohost 2] You could argue that. History has a funny way of repurposing old solutions for entirely new reasons.