Cohost 1: Okay, let’s unpack this. We’re kicking off a deep dive today that’s uh a little different.

Cohost 2: Mhm.

Cohost 1: It’s the starting point of a mission, really.

Cohost 2: Yeah.

Cohost 1: Understanding a specific place by peeling back its layers of history, you know, starting from the sources we have.

Cohost 2: Right.

Cohost 1: I actually live here in Warwick, Rhode Island, and well, as a relative newcomer, I’ve been determined to understand the deep history of this amazing area.

Cohost 2: And the request is straightforward, but honestly, deeply ambitious to accurately research the history of this region.

Cohost 1: Yeah.

Cohost 2: What’s fascinating here, looking at the sources, is you immediately see that to truly understand modern Warwick, well, you have to grasp the dramatic industrial history of its former half.

Cohost 1: The part that left.

Cohost 2: Exactly, the part that politically left, West Warwick, a community basically forged entirely by intense development along its uh its river system.

Cohost 1: Absolutely. So, I’m presenting this history based on the research I’ve pulled together from our sources. And look, I’m attempting to be as accurate as possible.

Cohost 2: Of course. History is tricky.

Cohost 1: It is. So, I really invite you, the listener, to follow along with me as I learn, and please offer any feedback or corrections on what we present here.

Cohost 2: Good approach.

Cohost 1: And our first big discovery, I think, is how the earliest history anchors this whole region to a figure of like national significance.

Cohost 2: Right, and that quickly sets the stage for, well, a century of industrial development that eventually created this permanent political split.

Cohost 1: So, where do we start? Way back.

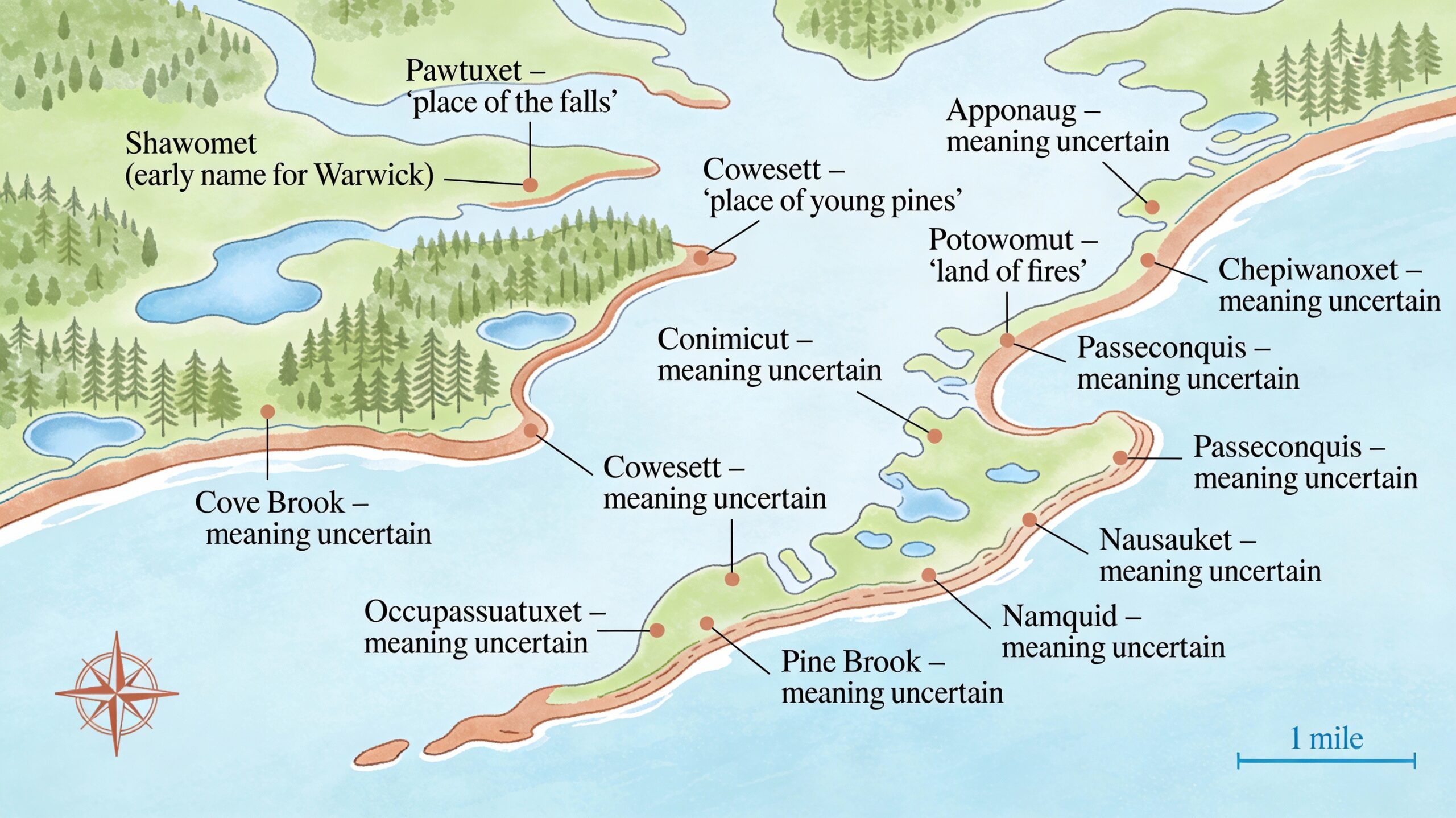

Cohost 2: Way back. This historical anchor point takes us well before the industrial age. Before West Warwick was even a thought, this land was part of the original Warwick purchase, 1642 Shawamet purchase.

Cohost 1: Okay.

Cohost 2: And the most famous figure to come out of that early colonial uh revolutionary context, Nathaniel Green.

Cohost 1: Ah, the American Revolution Powerhouse. Born in 1742 right here in Patuxet, which back then was part of Warwick.

Cohost 2: That’s him. He’s such an anomaly, isn’t he? When you look at where the area ended up, coming from that strict Quaker background.

Cohost 1: Preaching non-violence, yeah.

Cohost 2: Right. Minimal formal education.

Cohost 1: Mhm.

Cohost 2: And yet he becomes one of the sharpest military minds of his generation. It’s kind of amazing.

Cohost 2: It really is. And what’s fascinating is the sheer like individual drive it took to overcome that origin. He worked in his family’s successful iron forge business.

Cohost 1: Right, making chains, ship anchors.

Cohost 2: Uh-huh. Which sort of foreshadows the region’s industrial future in a way. But Green was fiercely self-taught, built up this huge personal library.

Cohost 1: Gave him the confidence, maybe the knowledge.

Cohost 2: I think so. The literary and strategic confidence he needed. This self-made man valuing, you know, personal industry over who your family was, he becomes George Washington’s de facto second in command, number two basically.

Cohost 1: So, you’ve got this foundational DNA rooted in that sort of self-made revolutionary grit.

Cohost 2: Mhm.

Cohost 1: But then how does that quiet rural place turn into something so utterly different, an urban industrial center, so different it actually breaks apart centuries later?

Cohost 2: Yeah, the leap is stark.

Cohost 1: Going from Nathaniel Green in 1742 straight to a political split in 1913. It’s jarring.

Cohost 2: That transformation, it’s entirely powered by economics and geography. The split itself wasn’t sudden, though.

Cohost 1: No.

Cohost 2: Oh, no, it was decades in the making. It reflected these deep, ultimately irreconcilable differences. You had the eastern part of old Warwick.

Cohost 1: Okay.

Cohost 2: That had the farms, the shore resorts, some newer suburban developments, politically pretty dominated by the Republican Party.

Cohost 1: And the western villages then, the ones that became West Warwick.

Cohost 2: Completely different picture. They were clustered along the Patuxet River, densely urbanized, heavily industrialized.

Cohost 1: Right.

Cohost 2: And leaned strongly democratic, you know, because of the huge mill worker population.

Cohost 1: So, what was the final straw? The thing that actually triggered the split?

Cohost 2: The core issue that finally pushed the 1912 referendum was, well, infrastructure and taxes.

Cohost 1: Ah, the classic conflicts.

Cohost 2: Exactly. The industrial West felt like they were paying way too much in taxes that mostly went to support services in the suburban East.

Cohost 1: While the East probably felt—

Cohost 2: The East felt the industrial development with all its immigrant populations and demands for schools, roads, sewers, was just draining resources. Their needs had simply diverged too much.

Cohost 1: So, West Warwick incorporates.

Cohost 2: Yeah.

Cohost 1: Becomes Rhode Island’s youngest town in 1913.

Cohost 2: That’s the moment. A political divorce basically.

Cohost 1: And that structural conflict, the reason that West transformed so dramatically, comes down to geography.

Cohost 2: Yeah.

Cohost 2: Purely geographical driver.

Cohost 1: Yep.

Cohost 2: Water power. West Warwick’s entire historical fate is dominated by the Patuxet River, that swift flow, especially where the north and south branches meet at River Point.

Cohost 1: So, the river is the engine.

Cohost 2: Absolutely. The transition from, you know, subsistence farming, growing corn, beans, raising oxen to heavy industry was uh shockingly rapid.

Cohost 1: When did it really kick off?

Cohost 2: The start date for the textile boom is usually pegged at 1794. That’s when Joe Green, a descendant of one of the original Warwick purchasers, built the cotton mill at Centerville.

Cohost 1: And that was early, right?

Cohost 2: Extremely early.

Cohost 1: Yeah. To put it in perspective, this was only the second spinning mill built in all of Rhode Island.

Cohost 1: Wow. In the birthplace of the American textile industry.

Cohost 2: Right here.

Cohost 1: I was stunned when I read this. By 1810, just 16 years later, five of the seven mills in the entire state operating over a thousand spindles, they were clustered right here in what becomes West Warwick.

Cohost 2: It’s incredible concentration.

Cohost 1: What was the specific advantage? Why this little valley over say Providence?

Cohost 2: It was the Patuxet’s consistent, reliable fall and flow. It provided perfect, cheap power, just ideal for textile machinery back then, and that attracted massive early investment.

Cohost 1: So, everyone jumped on it.

Cohost 2: Pretty much. The sources are clear. By 1840, every single suitable water power site in the area was already snapped up by textile manufacturers.

Cohost 1: Every single one.

Cohost 2: Which gave this area just an outsized role in the nation’s early industrial output.

Cohost 1: And this boom, it completely reshaped the landscape, didn’t it? By the late 1800s, those isolated farmsteads gone.

Cohost 2: Totally gone. In their place, you suddenly had these dense clusters of housing built right up against the factory gates, hugging the river banks.

Cohost 1: River housing.

Cohost 2: Mostly, yeah. And then roads started connecting these industrial nodes, these villages, essentially welding them together into one sort of cohesive urbanized zone, very distinct from the sprawling, less developed farmland over to the east.

Cohost 1: And it’s really crucial, I think, to understand that West Warwick isn’t just one thing. It’s like a federation of distinct mill villages.

Cohost 2: That’s a great way to put it. A federation.

Cohost 1: Each with its own character, all sprung up along the river branches. We’re talking about Centerville, Crompton, Natick, Phoenix, River Point, Clyde, Lippitt, and Arctic.

Cohost 2: And each village tells a slightly different part of the story, especially the labor history. Take Arctic.

Cohost 1: Yep.

Cohost 2: Was actually one of the last to really develop its core dates. It’s more to the 1850s, but quickly became the largest, the main commercial hub.

Cohost 1: Center of gravity.

Cohost 2: Exactly. And there’s that interesting story about its name.

Cohost 1: Oh, yeah.

Cohost 2: Apparently, the mill there was at the bottom of this steep slope that trapped cold air. People said it was the coldest spot around.

Cohost 1: Huh. So, Arctic.

Cohost 2: Arctic. And supposedly, it also rhymed nicely with the Spurr Company’s other factory names, which might have helped it stick.

Cohost 1: And by the 1920s, Arctic was really functioning as like Central Rhode Island’s Main Street, right?

Cohost 2: Absolutely. You had major commercial blocks, the Synott building, Cartier building, JJ Newberry store, real regional destinations. And the town put its civic center there too, the municipal building that’s still there today.

Cohost 1: But other villages had different timelines.

Cohost 2: Oh, yes. If you look south to Crompton, its industrialization started much earlier, around 1807 with a stone mill.

Cohost 1: Right.

Cohost 2: By 1860, Crompton already had four churches up and running, including St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church.

Cohost 1: Built in 1844.

Cohost 2: 45. That’s the one. And the sources say it’s the oldest existing Catholic church building in Rhode Island.

Cohost 1: Wow. And its construction really points to that dramatic shift in who was living there, right?

Cohost 2: Absolutely. That need for massive reliable labor, it fundamentally defined the town’s cosmopolitan identity. The sources really highlight this.

Cohost 1: West Warwick became one of the state’s most diverse communities.

Cohost 2: Hugely diverse. You see these successive waves of immigration pouring in to work the mills.

Cohost 1: Who came?

Cohost 2: Well, the Irish community arrived relatively early. They’re the ones who built St. Mary’s in Crompton. Later, you get large numbers of French Canadians, especially clustering in Arctic.

Cohost 1: And they built their own institutions.

Cohost 2: They did, often separate from the uh the dominant Irish Catholics initially. Then Italian families came, concentrating heavily in Natick. They built Sacred Heart Church there in 1929. Portuguese families settled largely in Phoenix.

Cohost 1: Any others mentioned?

Cohost 2: Yeah, the sources also mentioned folks from Sweden, Poland, Ukraine. It created this incredibly rich, but also very close-knit proximity of different cultures.

Cohost 1: Building this unique social tapestry in West Warwick.

Cohost 2: Completely setting it apart from its more sort of homogeneous eastern neighbor.

Cohost 1: But that high concentration, that reliance on one industry, it made the area productive, but also really vulnerable.

Cohost 2: Deeply vulnerable. That incredible boom, driven entirely by textiles, it eventually came to a grinding halt.

Cohost 1: And the sources emphasize this decline started before the Great Depression.

Cohost 1: Right.

Cohost 1: Hitting hard in the 20s and 30s.

Cohost 2: That’s key. It wasn’t just the depression. The economic problems in northern textiles, including West Warwick, started earlier. It wasn’t just southern competition either, though that was certainly a factor.

Cohost 1: What else is going on?

Cohost 2: Structurally, a lot of these New England mills just failed to vertically integrate, to modernize fast enough. They relied too heavily on, frankly, cheap immigrant labor and older machinery.

Cohost 1: So, when competition got tough.

Cohost 2: Exactly. When competition stiffened from the south and elsewhere and labor unrest grew, there were major strikes, wage cuts became necessary just to compete, and ultimately closures were inevitable.

Cohost 1: And we see that with specific mills.

Cohost 2: Graphically. The Natick Mills, for instance, so central to the town’s rise, closed in the 1920s, then destroyed by fire in 1941, just gone.

Cohost 1: Wow. But despite that huge industrial downturn, the physical history, it’s still there, isn’t it? Etched into the landscape, giving clues to that past.

Cohost 2: It absolutely is. When you drive through today, you can still see those uh utilitarian multi-family worker houses, lots of those long one and a half story duplexes.

Cohost 1: Built by the big textile firms, the Spragues, the Knights.

Cohost 1: Yeah. And the architecture tells a story too, right? About class.

Cohost 2: Oh, it speaks volumes. Those worker homes, built fast, built cheap, designed for maximum occupancy, minimum cost, they’re like the visual embodiment of industrial efficiency.

Cohost 1: Utilitarian is the word.

Cohost 2: Definitely. But then right alongside them, especially in villages like Phoenix, you find these much grander Greek revival homes.

Cohost 1: Built by—

Cohost 2: Successful mill agents, local merchants, the people who own things. They reflect the sort of established wealth, a desire for classical permanence right in the middle of all this rapid industrial change.

Cohost 1: That contrast really shows the divide between the people working in the mills and the people owning the mills.

Cohost 2: It’s written right there in the buildings.

Cohost 1: So, the industrial engine slows way down. The town has to shift its focus.

Cohost 2: It does. Today, West Warwick is working to diversify its manufacturing. You see chemicals, food products, metal fabrication now.

Cohost 1: And it’s kind of coalescing, right? Becoming one large urbanized area, more integrated with Providence.

Cohost 2: Exactly. It’s much more integrated into the whole Providence metro area now, less like those distinct separated mill villages of the past.

Cohost 1: But that modern shift, it brought new challenges too, didn’t it? Especially for those old village centers.

Cohost 2: It did, and they connect directly back to that old political divorce, interestingly enough. Places like Arctic, which were once these thriving regional shopping destinations.

Cohost 1: Yeah, Central RI’s Main Street.

Cohost 2: Right. Their commercial centers got hit hard by the rise of the big shopping malls. Malls built where? Mostly in nearby Warwick in the 60s and 70s.

Cohost 1: Ah. The parent town strikes back in a way.

Cohost 2: You could see it like that. And the new highway system, Route 95 and others, while they improved mobility overall, they also kind of bypassed and further undermined those old village commercial cores.

Cohost 1: Routing traffic and shoppers elsewhere.

Cohost 2: Precisely, away from Arctic, away from Phoenix Center.

Cohost 1: So, those commercial blocks that were once the heart of the region, they’re sort of relics now. Undermined by the suburban development patterns of the very town West Warwick split from decades earlier.

Cohost 2: Yeah.

Cohost 1: That’s ironic.

Cohost 2: It is deeply ironic. And if you connect all this to the bigger picture, West Warwick’s story is just this profound narrative. It’s about local geography creating for a time global economic power, which then generates immense social and demographic change, followed by structural economic failure, and ultimately that permanent political divorce.

Cohost 1: That’s a really powerful lesson in how industry shapes destiny for better and for worse.

Cohost 2: And it’ll run for worse.

Cohost 1: So, what does this all mean for us then? As we keep going on this journey of discovery, we’ve traced the history of this uh determined river-powered textile center. And I feel like we have a much clearer picture now of why modern Warwick and West Warwick look the way they do today, carrying both the scars and the successes of that Patuxet Valley history.

Cohost 2: Absolutely. And I think this raises a really important question for you, the learner, to consider as you actually look at the landscape today. Okay.

Cohost 1: When you navigate the modern streets, the new housing, the highway developments.

Cohost 2: Yeah.

Cohost 1: Can you still actually discern the exact boundaries? Sometimes they were quite narrow boundaries. Between the old villages.

Cohost 1: Yes. Between where the Irish, the Italian, the French Canadian, the Portuguese mill villages once stood. And maybe more importantly, what specific architectural details are still there? What clues remain that reveal this deep cosmopolitan industrial heritage? It’s history literally etched into the stone and brick of almost every village, just waiting, you know, to be rediscovered.