[00:00:00] Cohost 1: Welcome to the Deep Dive, where we take your source material and extract the history, strategy, and surprising personal truths you need to know.

[00:08:00] Cohost 2: Today we’re focusing on a really fascinating figure, Major General Nathaniel Green.

[00:12:44] Cohost 1: Right, a name you might know, but maybe he sits in that uh second tier of the revolutionary pantheon for a lot of people.

[00:19:30] Cohost 2: He absolutely does. Often overlooked for the let’s say flashier figures. But if you really look at what his contemporaries thought of him, the picture just completely changes.

[00:28:43] Cohost 1: And what was that picture?

[00:29:56] Cohost 2: I mean, we were talking about the man Alexander Hamilton praised by saying his name would at once awaken in your mind the images of whatever is noble and estimable in human nature.

[00:40:63] Cohost 1: Wow.

[00:41:22] Cohost 2: Yeah. That’s not the kind of language you use for a historical footnote. That is pure reverence for a strategic genius.

[00:47:31] Cohost 1: Absolutely. So our mission today is to go far, far beyond the standard biography. We’re going to dive into the the profound paradoxes that really defined him.

[00:56:88] Cohost 2: You mean like the wealthy Quaker who completely rejects pacifism?

[01:00:37] Cohost 1: Exactly. He becomes the fighting Quaker. And then he’s this brilliant field commander who also somehow revolutionizes logistics before earning the title Savior of the South.

[01:12:08] Cohost 2: It’s just a remarkably complex life. It’s marked by this incredible brilliance on the battlefield and then, well, crushing betrayal right after.

[01:20:25] Cohost 1: And the sources we have for this deep dive are pretty robust.

[01:22:74] Cohost 2: Oh, they are. We’re looking at core military histories that break down his adaptive leadership style, extensive biographical notes detailing his personal conflicts. I mean, everything from his expulsion from the Quaker faith to his post-war financial ruin.

[01:37:42] Cohost 1: And we also have some fascinating genealogical research that ties his family line directly to the present day.

[01:42:61] Cohost 2: Right. And we’ll even get into the complex story behind all the towns and counties that are named in his honor.

[01:47:37] Cohost 1: Okay, let’s unpack this journey and I think we have to start with the very surprising, very rigid environment that produced America’s uh ultimate non-traditional general.

[01:57:42] Cohost 2: Absolutely. Let’s start at the beginning.

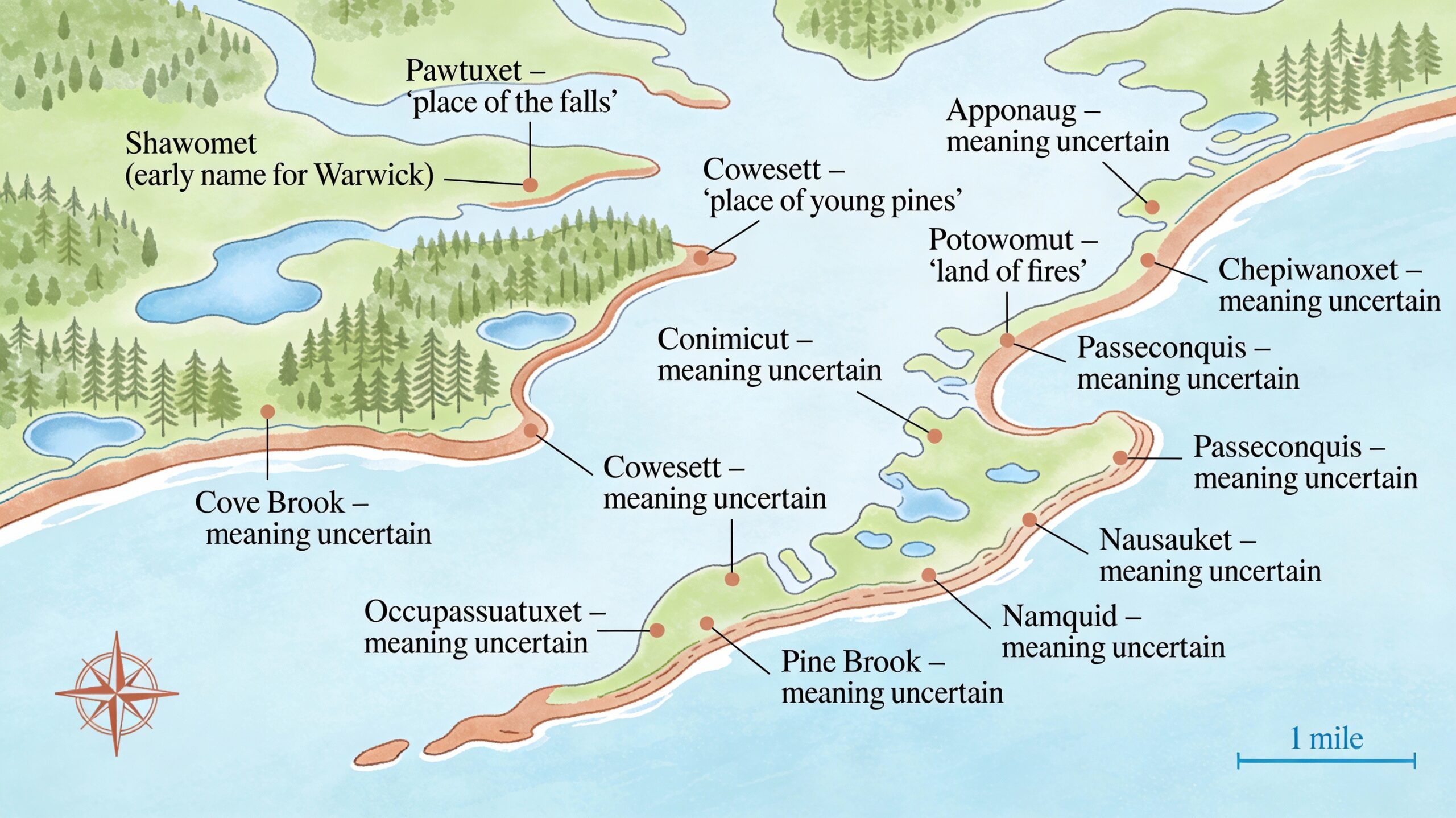

[01:58:85] Cohost 1: Nathaniel Green’s start in life. This is back in 1742 at Forge Farm in Warwick Rhode Island it was, well, it was privileged but it was also incredibly rigid.

[02:08:42] Cohost 2: That’s the perfect way to put it. His family was prosperous. They were deeply rooted in the Quaker faith and they worked as very successful merchants and farmers.

[02:16:81] Cohost 1: So this wasn’t a family just scrambling to survive.

[02:19:62] Cohost 2: Not at all. I mean, you have to understand, they were the established Warwick Greens. They were founding settlers of Rhode Island. Their lineage traces back to these really early colonial figures like John Green and Samuel Gorton.

[02:31:67] Cohost 1: So they had wealth, they had stability.

[02:33:88] Cohost 2: They had it all. But their entire existence was governed by the society of friends’ incredibly strict religious and moral rules. And the central one, the one that shaped everything was pacifism.

[02:46:50] Cohost 1: And that tenant, that rule just immediately clashed with Young Green’s natural curiosity, didn’t it?

[02:52:16] Cohost 2: Immediately. His father actively discouraged any intellectual pursuits that weren’t, you know, religious scripture. He called things like book learning and even dancing dangerous diversions.

[03:02:45] Cohost 1: For a young, obviously intelligent mind, that must have felt just incredibly stifling.

[03:07:98] Cohost 2: It created this huge internal conflict for him. But this is where you see his characteristic ingenuity, even as a young man. He somehow convinces his father to hire a tutor for the standard subjects.

[03:20:15] Cohost 1: Okay, so he gets a foot in the door academically.

[03:22:15] Cohost 2: He gets a foot in the door and then he leverages that access to just plunge into intense self-study of subjects that were completely removed from Quaker theology. We’re talking mathematics, classics, law, and most critically the works of the age of enlightenment.

[03:39:13] Cohost 1: So this intellectual foundation, which he basically had to build in secret, that’s what made him such an adaptive commander later on.

[03:44:66] Cohost 2: Without a doubt. It’s it’s really incredible to think that the man who would later out strategize Cornwallis was essentially teaching himself military theory by hiding books from his father.

[03:54:39] Cohost 1: Do we know what specific military texts he was drawn to? It really seems like he was preparing for a career that was, I mean, strictly forbidden by his entire culture.

[04:02:32] Cohost 2: He was in essence building an anti-quaker library. He just devoured military history and theory.

[04:08:18] Cohost 1: Any specific authors?

[04:09:88] Cohost 2: We know he studied Julius Caesar’s commentaries, which focus so much on speed and logistics. He read the works of Frederick the Great, the famous Prussian monarch who really emphasized maneuver warfare over just brute force.

[04:22:64] Cohost 1: And those are things you see in his campaigns later.

[04:24:64] Cohost 2: You see it everywhere. But perhaps the most influential was Maurice of Sachs’s reveries on the art of war. Sachs promoted these incredibly adaptive strategies that were tailored to terrain and climate. which is, you know, a foundational concept for Green’s later success in the unpredictable swamps of the south.

[04:43:24] Cohost 1: So his mind was already a strategic blueprint, years and years before he ever saw a battlefield.

[04:48:33] Cohost 2: It was. And in 1770, he sort of cements his independence. He moves to Coventry Rhode Island to manage the family’s foundry, which was thriving.

[04:57:33] Cohost 1: And that’s where he built his own home, Spell Hall.

[04:58:80] Cohost 2: That’s right, and it’s still stands today. But his public interests were just becoming impossible for his community to ignore. His intellectual fascination with conflict soon turned into active political engagement.

[05:11:42] Cohost 1: And this leads right to the the ultimate and I guess necessary contradiction in his life. He had to break with his faith.

[05:20:25] Cohost 2: It was inevitable. By July of 1773, he had drifted so far from pacifism, I mean, he was publicly endorsing the idea of war against Great Britain, that he was formally suspended from Quaker meetings.

[05:32:38] Cohost 1: And this wasn’t just a quiet departure, wasn’t it?

[05:34:39] Cohost 2: No, not at all. It was a public declaration. He was choosing military readiness over his own birthright, his own religion, his family.

[05:41:69] Cohost 1: And then he takes action the very next year. He helps establish and then joins the Kentish Guards militia unit in 1774.

[05:48:47] Cohost 2: This was the physical proof. This was the embodiment of his rejection of pacifism.

[05:52:84] Cohost 1: And his uh, his antagonism toward the British crown actually ran even deeper than just political philosophy, right? Our sources mentioned he was directly involved in some pre-war colonial resistance.

[06:02:77] Cohost 2: He was. He and his brothers were successful merchants and they initiated a pretty significant legal battle against a British official named William Duddington.

[06:10:48] Cohost 1: What was the issue?

[06:11:43] Cohost 2: Duddington had seized one of their ships, a vessel they owned, under some very questionable revenue laws. And Green being well versed in law, filed a lawsuit for damages.

[06:22:9] Cohost 1: And he won.

[06:22:42] Cohost 2: He won. and that successful legal challenge, you have to imagine, just amplified the political alienation in Rhode Island.

[06:29:64] Cohost 1: Right, because this is the same area where the Gasby affair happens.

[06:32:70] Cohost 2: Exactly. That lawsuit really helped set the stage politically. Didnington was the very same officer commanding the HMS Gasby, the British custom ship that famously ran a ground and was torched by a Rhode Island mob in 1772.

[06:48:33] Cohost 1: So Green was already known as a powerful opponent of British policies.

[06:51:50] Cohost 2: He was. He contributed to that really heated atmosphere that led to the Gasby affair, which was one of the earliest, most overt acts of revolutionary resistance.

[07:00:23] Cohost 1: And here’s the personal irony that we just have to mention. Despite being instrumental in forming this militia, the Kentish Guards and having studied military history so intensely, he was initially denied an officer’s commission in his own unit.

[07:11:79] Cohost 2: Yes. It’s almost unbelievable. And the reason was a slight limp that he’d had since childhood, probably from a bone infection or something similar.

[07:20:30] Cohost 1: So the militia officers decided a minor physical imperfection disqualified him from leadership.

[07:24:73] Cohost 2: They did. It’s truly amazing that a man who would become Washington’s most indispensable general was initially deemed unfit to lead a local company of men, just based on that detail. It really makes his rapid ascent all the more impressive.

[07:40:15] Cohost 1: Yeah, it really does. And that physical constraint was of course very quickly overridden by military necessity.

[07:44:81] Cohost 2: As soon as the shooting started. Yes.

[07:46:58] Cohost 1: When Lexington and Concord exploded in April 1775, Green’s rise was just meteoric. It proves that intellectual preparation beats, you know, physical perfection any day.

[07:57:42] Cohost 2: Well, Rhode Island certainly thought so. They immediately recognized his competence and appointed him commander of their entire colonial army.

[08:04:41] Cohost 1: And that recognition just catapulted him straight into the highest levels of the Continental Army.

[08:09:39] Cohost 2: Straight to the top. By June of 1775, he’s appointed Brigadier General under George Washington. He actually missed the Battle of Bunker Hill, but he quickly joined Washington during the siege of Boston. and Washington saw something in him immediately.

[08:24:25] Cohost 1: What do you think that was?

[08:25:28] Cohost 2: An intelligent, disciplined mind that was completely focused on strategy, not just on, you know, battlefield glory.

[08:32:51] Cohost 1: It wasn’t long before Washington promoted him to major general. Our sources are very clear that Green became one of Washington’s most trusted confidants, relied upon not just for executing orders, but for actually helping to formulate them.

[08:45:64] Cohost 2: Washington really appreciated that Green, despite his total lack of traditional military training, was just intensely insightful. He thought differently.

[08:53:57] Cohost 1: And their bond was really forged in the fire of those chaotic early years, especially during the New York and New Jersey campaigns.

[08:59:60] Cohost 2: Oh, absolutely. Green was tasked with some crucial defensive measures there, supervising the fortifications all around Manhattan and Long Island.

[09:07:65] Cohost 1: But this high pressure period also sees the first of his major career setbacks. It starts with a serious fever that causes him to miss the disastrous battle of Long Island.

[09:17:66] Cohost 2: Yeah, and once he recovered from that, he dives right into the strategy of withdrawal. After the retreat from Long Island, Green proposed this this almost scorched earth policy. He urged Washington to raise Manhattan completely.

[09:32:82] Cohost 1: Just burn the city to the ground.

[09:34:25] Cohost 2: To the ground. His rationale was pure military necessity. Deny the British the use of that crucial city as a base of operations and more importantly as winter quarters.

[09:44:83] Cohost 1: But Congress, of course, fearing the political and economic blowback of destroying one of America’s major cities, they forbade the action.

[09:51:59] Cohost 2: A pragmatic military decision overturned by political considerations. A story as old as time.

[09:56:49] Cohost 1: Exactly. And while they were withdrawing from Manhattan, Green finally saw his first real combat experience at Harlem Heights.

[10:02:49] Cohost 2: Which was a minor but, you know, strategically important American victory. It was a morale booster. But that initial success was very quickly overshadowed by the catastrophe that almost ended his relationship with Washington.

[10:14:87] Cohost 1: The Fort Washington failure. November 1776.

[10:18:78] Cohost 2: That’s the one. And you really have to understand the details because it highlights Green’s early, well, maybe arrogance, combined with Washington’s unwavering trust.

[10:28:49] Cohost 1: So Green was in command of Fort Lee and Fort Washington, these key fortifications on opposite sides of the Hudson River.

[10:34:86] Cohost 2: Right. And Washington had serious, serious reservations about the one on the Manhattan side, Fort Washington.

[10:40:53] Cohost 1: Why was that?

[10:41:19] Cohost 2: Washington explicitly suggested removing the garrison. He noted the fort’s vulnerability and its, uh, its inability to actually block the British Navy effectively, especially after the British had secured control of all the surrounding high ground.

[10:56:20] Cohost 1: So the fort was basically useless.

[10:57:48] Cohost 2: strategically, yes. But Green, based on his own reading of the train and maybe a touch of overconfidence from his quick rise, he argued that they could hold it. He deferred Washington’s advice and made the decision to keep the 3,000 man garrison station there.

[11:12:35] Cohost 1: And the result was the worst defeat of the war in terms of men capture.

[11:16:32] Cohost 2: An absolute unmitigated disaster. The British swarm the fort and took 3,000 continental soldiers prisoner along with massive stores of weaponry and supplies.

[11:27:54] Cohost 1: The criticism of Green must have been immediate and just scathing.

[11:31:63] Cohost 2: It was monumental. But here is the profound lesson about leadership and about loyalty. Washington stood by him.

[11:39:23] Cohost 1: He didn’t fire him?

[11:39:87] Cohost 2: He refused to relieve Green of command. He understood that even the sharpest minds make catastrophic errors and he knew that Green’s overall strategic value far outweighed this single tactical blunder.

[11:51:71] Cohost 1: And Green repaid that loyalty.

[11:52:69] Cohost 2: He did. He served with distinction during the counter offenses at Trenton and Princeton, the very battles where Washington’s reputation was basically saved and restored.

[12:01:25] Cohost 1: So Green proved himself in the field, but his next major role was a deep dive into the, uh, the organizational machinery of war. In March of 1778, he reluctantly accepted the position of Quartermaster General.

[12:13:31] Cohost 2: And reluctantly is a huge understatement. This was seen as a demotion. It was a staff role, far from the glory of the field.

[12:18:24] Cohost 1: But it was arguably the single most crucial non-combat role in the entire army.

[12:22:45] Cohost 2: It was everything. especially given the starvation at Valley Forge, the previous winter. The army was literally falling apart because it couldn’t be supplied.

[12:30:74] Cohost 1: This role dealing with the brutal realities of logistics must have been an absolute masterclass in practical administration for him.

[12:37:62] Cohost 2: It was, and it absolutely solidified his reputation as a logistics genius. The challenges were just staggering. I mean, you have to picture it. The continental currency was collapsing, state governments were reluctant to part with any supplies, and the transportation infrastructure was practically non-existent.

[12:54:33] Cohost 1: So Green basically had to invent the entire supply chain from scratch.

[12:57:86] Cohost 2: He did. He completely reorganized the 3,000 person department, creating clear lines of authority where before there was just chaos.

[13:06:21] Cohost 1: Can you elaborate on the practical steps he took? I mean, what specifically did he change to bring order to that chaos?

[13:13:48] Cohost 2: Well, he established a clear layered system. First, he was smart enough to know he couldn’t do it alone, so who brought in seasoned administrators like Charles Pet and John Cox as his assistants. That freed him up to focus on the big picture, the strategy and the high-level negotiations with state legislatures.

[13:29:83] Cohost 1: Okay, so he delegated. What else?

[13:31:73] Cohost 2: Second, and this was key. He established these crucial centralized supply depots far away from the front lines in strategic defensible locations, places like Morristown and Reading. This was to ensure a steady, secure flow of provisions, ammunition and clothing.

[13:48:35] Cohost 1: And before Green, it was just catch as catch can.

[13:51:41] Cohost 2: Completely haphazard. Supplies were often just seized on the spot from local farmers, which created huge resentment. He brought structure and really foresight to the entire process.

[14:01:46] Cohost 1: So, wait a minute, he was still a field general attending Washington’s councils of war while at the same time running this gigantic 3,000 person supply chain? How did he manage both of those high pressure roles?

[14:12:87] Cohost 2: That’s the crucial point about Green’s unconventional nature. He just did. He continued to attend those war councils, despite technically being a staff officer. Washington valued his strategic insight above any staff title.

[14:26:54] Cohost 1: So Green could analyze a potential battle not just in terms of terrain, but in terms of sustainability.

[14:31:97] Cohost 2: Precisely. He’s thinking, how long can the troops stay there? Where will the supply wagons come from? What’s the forage situation for the horses? Very, very few commanders had that kind of holistic 360 degree view of warfare.

[14:45:51] Cohost 1: But the financial realities of the war eventually broke him even in this administrative role.

[14:49:95] Cohost 2: They did. Congress, which lacked the power to tax, simply couldn’t fund the supplies. This led Green to become a furious outspoken advocate for a stronger national government.

[15:00:85] Cohost 1: And his frustration just boiled over in 1780.

[15:03:31] Cohost 2: It did. The financial burden and the complete lack of institutional support just drove him to resign from the Quartermaster role. And his resignation letter was volcanic.

[15:12:38] Cohost 1: He didn’t hold back.

[15:13:79] Cohost 2: No, not at all. He heavily criticized Congress for its incompetence and its lack of financial support for the troops. He came perilously close to losing his commission entirely for insubordination.

[15:26:65] Cohost 1: And once again, Washington had to step in.

[15:29:40] Cohost 2: Once again, Washington had to personally intervene to save his career.

[15:33:57] Cohost 1: That experience as Quartermaster General must have demanded some really difficult moral choices, particularly when it came to foraging. We talk about the starvation at Valley Forge. Green had to be the man who kept the army alive by essentially seizing goods from local citizens.

[15:48:92] Cohost 2: He had to be ruthless for the greater good of the revolution. And this is where you see the immense personal toll of his duty. He wrote about the necessity of this seizure, noting the distress of the citizens.

[16:00:8] Cohost 1: What did he say?

[16:00:46] Cohost 2: He wrote, “Like a Pharaoh, I hardened my heart.”

[16:02:88] Cohost 1: Wow.

[16:03:68] Cohost 2: That single line just reflects the emotional weight of sacrificing personal morality and compassion for strategic survival. He had to be the villain in the eyes of the very people he was fighting to free just to keep the army in the field.

[16:16:13] Cohost 1: It’s clear that his expertise was not just in movement and supply, but in making these these impossible decisions.

[16:22:21] Cohost 2: It is. And that knowledge, that total understanding of logistics made him the only choice for his next and most important assignment.

[16:29:83] Cohost 1: So, by October of 1780, the war in the South had completely collapsed.

[16:33:63] Cohost 2: It was a disaster zone. The Continental Army had suffered these just devastating defeats at Charleston under General Lincoln and more recently at Camden under Horatio Gates.

[16:43:53] Cohost 1: So the British led by Lord Cornwallis, they basically controlled Georgia and South Carolina.

[16:49:57] Cohost 2: They did. It was a crisis of the highest order. So Washington appoint Green Commander of the Southern Department on October 14th, 1780.

[16:56:88] Cohost 1: And what exactly did he inherit?

[16:58:34] Cohost 2: He inherited what he himself called an army that was wretched beyond description. His 2300 men were starving, they were poorly equipped, and they were utterly demoralized. And they were facing Cornwallis’s numerically superior well-supplied force of 6,000 troops.

[17:14:18] Cohost 1: So winning by conventional means was just off the table.

[17:17:34] Cohost 2: Completely impossible. He couldn’t afford a single defeat. This required that adaptive leadership style, what our sources called solving complex wicked problems. He understood immediately that his objective was not to win battles, but to win the strategic war.

[17:33:38] Cohost 1: And his strategy was revolutionary. He called it a fugitive war.

[17:36:99] Cohost 2: Which was essentially a sophisticated, large-scale guerrilla warfare or a war of attrition. He was going to use space and time as his primary allies. The goal was to augment his own capabilities, relying on local militia and mobility, and then to patiently wait for Cornwallis to make an irreversible tactical error.

[17:55:82] Cohost 1: This is where we get the analogy of the marathon versus the sprint. Green wasn’t trying to win the sprint, the pitched battle.

[18:01:75] Cohost 2: No, he was forcing Cornwallis to run a supply marathon until he collapsed from exhaustion.

[18:06:40] Cohost 1: And to enhance his own army’s mobility, he used river boats a lot.

[18:09:82] Cohost 2: Heavily, especially the shallow draft Durham boats. He used them to quickly move supplies and men across the vast swampy waterways of the Carolinas, which denied the British an easy line of pursuit.

[18:20:41] Cohost 1: His very first move, when he got to Charlotte in December of 1780, it defied everything he had learned studying classical military texts. He deliberately split his already small, weak army.

[18:31:85] Cohost 2: It was a move of pure brilliance and confidence. He took his main contingent southeast, while sending General Daniel Morgan’s smaller, more elite detachment southwest. He was essentially offering Cornwallis two targets to chase.

[18:45:90] Cohost 1: When all the books say a weaker force should never ever divide.

[18:50:11] Cohost 2: But Green realized that dividing his force actually multiplied the problems for Cornwallis. And Cornwallis fell for it. He divided his own stronger forces sending his notorious cavalry commander Banister Tarton after Morgan.

[19:02:37] Cohost 1: Which leads directly to the Battle of Cowpens in January 1781.

[19:06:21] Cohost 2: A masterpiece of tactical maneuvering by Morgan. He used this genius tactic, the double envelopment, where he placed his militia in the front line with explicit instructions to fire only two volleys and then retreat.

[19:16:50] Cohost 1: A feined retreat.

[19:17:41] Cohost 2: A feined retreat which drew Tarton’s disciplined red coats right into the continental regular army who were hidden in reserve. The result was a crushing victory for the Americans and the near total destruction of Tarton’s force.

[19:31:48] Cohost 1: That defeat must have enraged Cornwallis. He realizes he has to crush Green immediately.

[19:36:76] Cohost 2: He does. And this is where he makes his faithful decision. He decides that speed is everything. So he burns his own baggage train.

[19:44:81] Cohost 1: He burns his own supplies.

[19:46:13] Cohost 2: Destroys all unnecessary supplies, food, tents, everything, just to speed up his pursuit of Morgan and Green. It was a critical mistake because he stripped himself of the logistical capacity he would need for the long chase that was coming.

[19:59:36] Cohost 1: And thus began the great race, or what some called the masterpiece retreat. Green led Cornwallis on this strategic withdrawal across North Carolina, heading for the Dan River.

[20:10:39] Cohost 2: The tactical genius of this retreat lay entirely in geography and timing. Green was using all his quartermaster knowledge to the absolute fullest. He had supply points pre- established exactly where he needed them.

[20:21:82] Cohost 1: So he was pulling Cornwallis further and further from the British supply bases in Charleston and Wilmington.

[20:27:56] Cohost 2: Exactly, leading him across this vast network of rivers in the middle of a wet winter. Green’s men used those pre-positioned boats to cross the swollen Dan River on February 14th, leaving Cornwallis maroon on the opposite bank, exhausted, hungry, and miles from help.

[20:44:31] Cohost 1: And Alexander Hamilton, who was not a man given to exaggeration, called that retreat a masterpiece of military skill and exertion.

[20:52:13] Cohost 2: It absolutely was. Cornwallis was strategically defeated by geography before the next major battle even happened. He couldn’t sustain the chase. His army was starving, exhausted, and now so far from any supply lines, he had to retreat south to Hillsborough.

[21:07:11] Cohost 1: So Green had destroyed Cornwallis’s momentum and his supply chain.

[21:10:65] Cohost 2: Completely. And just eight days later, Green crosses back over the Dan River ready to fight, but now on his own terms.

[21:17:15] Cohost 1: Which brings us to the Battle of Gilford courthouse on March 15th, 1781. Green had received enough militia reinforcements by then to swell his ranks to about 4,000 men.

[21:27:36] Cohost 2: Right. But he knew he was still facing superior British regulars. But he had calculated the cost. He didn’t need a definitive tactical victory. His objective was attrition.

[21:37:83] Cohost 1: So he deploys this brilliant defense in depth strategy using three defensive lines, a concept you said was inspired by ancient military thinking.

[21:47:19] Cohost 2: Right. It’s reminiscent of Hannibal strategy at the battle of Zama where he used his inferior troops first to absorb the initial Roman shock.

[21:55:20] Cohost 1: Okay, so clarify that for us. What does a defense in depth look like in practice, especially when you’re using unreliable militia.

[22:02:40] Cohost 2: Well, in a standard engagement, the weakest troops, the militia, they flee quickly. And that compromises the whole line. Green’s genius was that he planned for their retreat.

[22:12:35] Cohost 1: So he used their weakness as a strength.

[22:13:84] Cohost 2: precisely. The first line was North Carolina militia placed openly in the forest. Their instruction was simple. Fire two volleys at close range, then quickly retreat through pre-planned gaps in the lines behind them. This forced the British to absorb casualties and break their perfect formation.

[22:28:44] Cohost 1: So the first line was essentially sacrificial. It was designed only to inflict initial damage and fatigue.

[22:34:25] Cohost 2: Exactly. The second line, which was Virginia militia, was placed further back. They were tasked to hold longer inflicting more serious damage. So by the time the British finally reached Green’s third line, his continental army regulars, they were exhausted, depleted and completely disorganized from fighting their way through two separate layers of intense, unexpected resistance.

[22:55:54] Cohost 1: The battle itself was a blood bath. When the fighting reached that third line, it became incredibly fierce.

[23:01:76] Cohost 2: It did. And in a moment of sheer desperation and just horrific calculation, Cornwallis ordered his artillery to fire grape shot, a massive cluster of small iron balls directly into the thick of the melee.

[23:13:58] Cohost 1: Hitting his own men.

[23:14:48] Cohost 2: Hitting his own men and the Americans, indiscriminately. Green saw the devastating carnage, realized Cornwallis was strategically shattered, and he ordered a retreat. He saved his army intact, ready to fight another day.

[23:27:26] Cohost 1: So technically the British held the field, that makes it a tactical victory for Cornwallis, but strategically it was what’s called a pyric victory.

[23:35:63] Cohost 2: A classic Pyric victory. The cost to the British was devastating. Cornwallis lost nearly 25% of his entire command, about 500 men killed and wounded, including many of his senior officers.

[23:48:38] Cohost 1: An unrecoverable loss.

[23:49:85] Cohost 2: Absolutely unrecoverable. Yeah. A pyric victory is one you gain at such a high cost that it amounts to a strategic defeat because you lose the capacity to sustain the war effort. Cornwallis was forced to choose, try to limp back to Charleston for supplies or push north to Virginia.

[24:07:44] Cohost 1: And he chose Virginia.

[24:08:70] Cohost 2: He chose Virginia, which led him directly into the trap at Yorktown.

[24:12:13] Cohost 1: And the genius continues because Green didn’t follow Cornwallis. He stayed in the south to capitalize on the power vacuum.

[24:19:62] Cohost 2: He continued his fugitive war, constantly engaging and maneuvering. And while he suffered technical defeats at places like Hobkirk’s Hill and failed to capture the fort at the siege of 96, these tactical setbacks were strategically meaningless.

[24:32:11] Cohost 1: Because by keeping the pressure on, he forced the British to abandon their posts.

[24:36:20] Cohost 2: Right. The British General Rodin left Camden. The British gave up 96 shortly after the failed siege. By mid-1781, thanks to Green’s relentless pressure and the efforts of his subordinates, the British controlled little more than the coastal cities of Charleston and Savannah.

[24:52:95] Cohost 1: The final major engagement was the Battle of Utah Springs in September 1781.

[24:58:20] Cohost 2: And once again, the continentals retreated from the field. But the British suffered quote, more substantial losses, which forced them to withdraw all the way back to Charleston. Congress considered this such a strategic success, forcing the British to surrender the entire interior of the south that they issued Green a gold medal and congratulated him for the victory.

[25:19:15] Cohost 1: So Green really secured his legacy as the savior of the South. He made sure that while Washington delivered the final decisive blow at Yorktown, the South had already been won through a strategy of maneuver and attrition.

[25:29:48] Cohost 2: His whole approach is just perfectly encapsulated in that defiant motto of his. We fight, get beat, rise and fight again.

[25:37:37] Cohost 1: After the war was concluded, Green was celebrated as a hero as you’d expect. He was rewarded handsomely by the states he’d saved.

[25:44:31] Cohost 2: Very handsomely. North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia all voted him these liberal grants of land and money. That included the sprawling Boons Barony in South Carolina and the magnificent Mulberry Grove plantation near Savannah, Georgia.

[25:58:21] Cohost 1: But despite these generous tokens of appreciation, Green’s personal life was just swiftly consumed by this agonizing decades long financial disaster.

[26:07:54] Cohost 2: And it stems directly from his time as a general, from his logistical genius during the war.

[26:12:70] Cohost 1: So let’s talk about the mechanics of this ruin because it’s really a tragedy of bureaucratic indifference. It comes from his time supplying the army in Charleston in 1782 and 1783. What did he do with those contracts that led to his downfall?

[26:25:70] Cohost 2: Well, the army was perpetually starved for funds, even as the fighting was winding down. And to ensure his troops, who were basically just waiting to be discharged, remained fed and disciplined, you know, to prevent a mutiny or mass desertion, Green felt morally obligated to guarantee their supplies.

[26:41:40] Cohost 1: So he personally bonded contracts with a private company, Banks and Company.

[26:45:26] Cohost 2: Exactly. He was essentially using his own personal wealth and his own credit as collateral to guarantee payment for the supplies being delivered to the army.

[26:54:19] Cohost 1: He was taking on the government’s financial risk to save his army, believing the government would immediately reimburse him.

[27:00:27] Cohost 2: Of course. But the contractor defaulted. And because Green’s personal signature was on the bond, the creditors came after him personally. He was held responsible for this massive, massive debt.

[27:12:35] Cohost 1: And Congress?

[27:13:35] Cohost 2: Congress eventually ruled against the defaulting contractor, but the process was agonizingly slow. In the meantime, Green was left holding the financial bag.

[27:22:64] Cohost 1: The legal battle over the land sales granted to him dragged on for decades, long after he died.

[27:27:77] Cohost 2: Oh, for decades, from 1788 all the way until 1854, his affairs were just tied up in court. It was a nightmare of shifting state boundaries, complicated title disputes, partly involving British creditors who had prior mortgages on the lands and just complete bureaucratic apathy.

[27:43:53] Cohost 1: And the ultimate outcome, which was secured through a congressional relief act, was that his heirs received only a fraction of what they were owed.

[27:50:85] Cohost 2: A tiny fraction, about $2,000 instead of the anticipated 2400 pound sterling. The vast majority of the land had to be sold at a loss or was just tied up in legal claims.

[28:02:40] Cohost 1: It’s a truly heartbreaking irony. The man who ensured the survival of the Continental Army was himself ruined by the financial instability of the very nation he helped to found.

[28:12:11] Cohost 2: And his postwar struggles weren’t just limited to money either. In 1785, he faced a very serious and potentially deadly challenge to his honor from a Georgia senator named James Gunn.

[28:24:20] Cohost 1: What was the origin of that? It was something minor but politically charged, right? An incident involving the sale of war horses back in ’82.

[28:30:86] Cohost 2: That’s right. Gunn felt he’d been slided by Green’s handling of the disposition of these horses and he just escalated the issue dramatically.

[28:38:71] Cohost 1: So he challenged Green to a duel.

[28:40:47] Cohost 2: He did. He sent a threatening letter and then formally challenged him. And you have to remember, duels were a common almost mandatory way to resolve issues of honor among gentlemen and officers at the time. Refusing one could brand you a coward for life.

[28:55:27] Cohost 1: But Green made a crucial decision on the advice of General Anthony Wayne to refuse the challenge. And his reasoning was profound. It wasn’t about cowardice.

[29:03:76] Cohost 2: No, it was about protecting the military command structure of the new nation. He said he refused to establish a precedent for subjecting superior officers to the call of inferior officers for what the former have done in the execution of their public duty.

[29:18:59] Cohost 1: So he saw it as an attempt to undermine the authority of a commanding general.

[29:22:36] Cohost 2: A firm stand for the necessity of protecting commanders from retaliatory challenges by disgruntled subordinates. It was a big deal.

[29:29:60] Cohost 1: And though Washington assured him his reputation was intact, the tension was real. Both men lived in this Savannah area.

[29:36:13] Cohost 2: It was very real. Green reportedly carried pistols with him constantly, worried about a non-formal ambush from Gunn.

[29:42:51] Cohost 1: Sadly, his life was cut short shortly after that in 1786. He was remarkably young, only 43, at Mulberry Grove.

[29:50:23] Cohost 2: He succumbed to sunstroke after riding through the oppressive Georgia heat on June 12th. Some contemporary accounts even suggest he might have intentionally avoided riding after dark because of the lingering threat from gun, which would have forced him into the heat of the day.

[30:04:19] Cohost 1: And his burial, immediately following his death, offers one of history’s most bizarre twists.

[30:09:47] Cohost 2: It really does. His remains were initially interred in Savannah’s Graham Vault, where, incredibly, he rested alongside his arch rival from the war, the British General John Maitland.

[30:21:13] Cohost 1: In the same tomb?

[30:21:71] Cohost 2: In the same tomb for over a century until 1902 for his remains to be officially identified and finally moved to the dedicated Nathaniel Green Monument in Johnson Square in Savannah.

[30:32:48] Cohost 1: Wow. Well, the nation he helped save did repay him, at least geographically with immense honor. The list of places named after him is enormous.

[30:41:20] Cohost 2: It is. 14 US counties, including the most populous one, Green County, Missouri, plus just countless cities and towns.

[30:47:75] Cohost 1: And this brings us to that fascinating local mystery in North Carolina, the city of Greensboro. It was named to honor General Nathaniel Green for his crucial actions at the Battle of Gilford courthouse.

[30:59:75] Cohost 2: It was. But the question remains, where is the final E? The original documents all refer to the place as Greensboro. Over time, the name got shortened, which has led many people to mistakenly believe it’s named for the color or the landscape, you know, the greenboro, rather than for the general.

[31:18:78] Cohost 1: Why did they drop the E when other Greensbergs and Greensboros kept it?

[31:22:64] Cohost 2: It remains an unresolved historical puzzle. And what’s really interesting is the inconsistency. You can still find many local landmarks there that retain the original spelling, Green Street, Green Township, and the Nathaniel Green School. It’s a testament to how even a clear historical fact can become obscured by shifting local conventions.

[31:41:19] Cohost 1: And finally, we just have to note the profound historical ripple effect of the land grants he received. His original home, Spell Hall in Coventry, Rhode Island, is meticulously preserved today as the General Nathaniel Green Homestead Museum.

[31:53:93] Cohost 2: It is. But the Georgia plantation, Mulberry Grove has its own unique place in American economic history. Just seven years after Green’s death, the family hired a young Yale graduate named Eli Whitney to tutor Green’s children.

[32:08:24] Cohost 1: Eli Whitney.

[32:08:70] Cohost 2: Eli Whitney. It was there at Mulberry Grove in 1793 that Whitney invented and produced the cotton gin, a machine that would fundamentally transform the southern economy and subsequently the entire trajectory of the United States.

[32:22:50] Cohost 1: Incredible. So let’s transition now from the massive impact of Green’s public life to the intricate detailed detective work of connecting his family line to a modern descendant. This is the kind of genealogical aha moment that researchers live for.

[32:36:28] Cohost 2: Right. And this is a classic example of how historical noise, things like misinterpretation, incomplete records and very common names, can obscure a clear family connection. The quest started with persistent family lore that claimed a link to Major General Nathaniel Greene.

[32:50:56] Cohost 1: And the initial discrepancy, the first roadblock came from a family history written way back in 1908 by a William Henry Green.

[32:56:56] Cohost 2: That’s right. William Henry claimed that the Major General was a cousin of his great-grandfather, a man named Christopher Green. Unfortunately, later transcriptions of this handwritten note mistook it and assigned the relationship as first cousin.

[33:11:51] Cohost 1: And that seemingly small error in terminology creates a huge genealogical problem.

[33:16:35] Cohost 2: A major roadblock. First cousins share grandparents. Third cousins share great great grandparents. Our research confirmed that Nathaniel and Christopher were actually third cousins. They both belong to the same generation number five in the famous Warwick Green line.

[33:31:10] Cohost 1: And the common ancestor, the root of the US branch of the Warwick Greens was a John the Surgeon Green, who emigrated to Massachusetts Bay around 1635.

[33:39:55] Cohost 2: Right. And tracking back to this common ancestor requires navigating centuries of incomplete or conflicting records.

[33:45:62] Cohost 1: And the initial difficulty was just the overwhelming repetition of names.

[33:49:57] Cohost 2: A genealogist’s nightmare. In that specific line, there were multiple Christophers, multiple Williams, multiple Jonathans. And William Henry Green’s memoir didn’t list ancestors beyond his great-grandfather, Christopher. And while the General’s papers documented his immediate family, they didn’t extend far enough down the cousin lines to definitively link the two.

[34:10:37] Cohost 1: So how did the researcher cut through that noise? They were looking for a literal needle in a historical haystack. They needed an anchor point that was unique.

[34:18:72] Cohost 2: And the breakthrough came via two methods. First, they cross referenced with a definitive secondary source, a book called the Greens of Rhode Island, which was published in 1903 by another general, George Sears Green, and it mapped out the entire Warwick lineage.

[34:33:35] Cohost 1: And the second method?

[34:34:15] Cohost 2: A clever detective tactic, hunting for unusually named ancestors.

[34:38:64] Cohost 1: And the specific unusual name they found was Uncle Leander Green.

[34:41:88] Cohost 2: Exactly. Leander is rare enough to be an excellent marker. The researcher found a Leander Green in the family tree established by that authoritative GS Green book. This Leander, whose parents were William Green and a Mrs. Weaver, matched the family’s known details perfectly.

[34:59:66] Cohost 1: So by following that thread upward,

[35:01:21] Cohost 2: they confirmed that Leander’s father, William, had a father named Christopher Green, the correct Christopher Green, who was indeed a third cousin to the Major General.

[35:11:3] Cohost 1: And that successful connection also solved another charming piece of family lore that was mentioned in William Henry’s memoir, the identity of someone called Aunt Wiger.

[35:19:35] Cohost 2: Yes. The connection confirmed that Aunt Wiger was actually Lucy Green, who was Christopher’s daughter and she had married a man named Eli Wiger. All the small personal details finally clicked into place thanks to that one unique name, Leander.

[35:33:78] Cohost 1: So, the final genealogical nugget, the confirmed relationship connecting the researcher to the famous general, is that the modern descendant is a third cousin seven times removed of Major General Nathaniel Green.

[35:45:10] Cohost 2: All tracing back through John the Surgeon. A perfect illustration of how critical primary source data combined with clever detective work can transform family tradition into documented history.

[35:57:13] Cohost 1: So we began this deep dive with Nathaniel Green, the fighting Quaker, who rejected the pacifism of his birthright to become Washington’s strategic right hand.

[36:05:43] Cohost 2: And we’ve seen how his intellectual foundation led him to revolutionize supply chains and master the complex art of maneuver warfare.

[36:12:47] Cohost 1: He was the logistics master who kept the Continental Army alive and the strategic genius whose fugitive war won the south by prioritizing attrition over any immediate tactical victory.

[36:23:68] Cohost 2: He really is the commander whose leadership prevented the entire war from dissolving into chaos, even when the government completely failed to fund him.

[36:31:63] Cohost 1: And yet his post-war life stands as this profound tragedy, a man utterly defeated not by the British army, but by bureaucratic incompetence and bad contracts, which left him in debt until decades after his death.

[36:43:17] Cohost 2: And that brings us to our final provocative thought for you to consider. Green demonstrated that one can win a war through comprehensive strategy, even while losing the individual battles and incurring a heavy personal cost.

[36:56:66] Cohost 1: So, how does Green’s example where his strategic success against a superior foe came at the cost of profound personal financial ruin? How does that challenge our modern definition of a successful military or even political leader?

[37:10:14] Cohost 2: Was his ultimate crucial victory worth the decades of debt and legal battles that followed for his family? And if strategic genius sometimes requires taking on the moral and financial burdens that the state refuses to carry? Well, what does that say about the true cost of liberty?

[37:25:29] Cohost 1: Something to ponder as you reflect on the difference between tactical glory and true strategic mastery.

[37:30:46] Cohost 2: Thank you for joining us for this deep dive.

[37:31:61] Cohost 1: We’ll see you next time.