Cohost 1: Welcome back to the deep dive. Today we are uh strapping in for a bit of a chronological journey. We’re looking at public space development in Warwick, Rhode Island.

Cohost 2: Yeah, and our mission, it sounds simple maybe, but it’s tracing how two really different coastal properties became public parks.

Cohost 1: Right. One was this um immediate big donation, a memorial.

Cohost 2: And the other?

Cohost 2: Well, that one went through a much longer kind of turbulent process, decades of being something else entirely before it was, you know, reclaimed for the public.

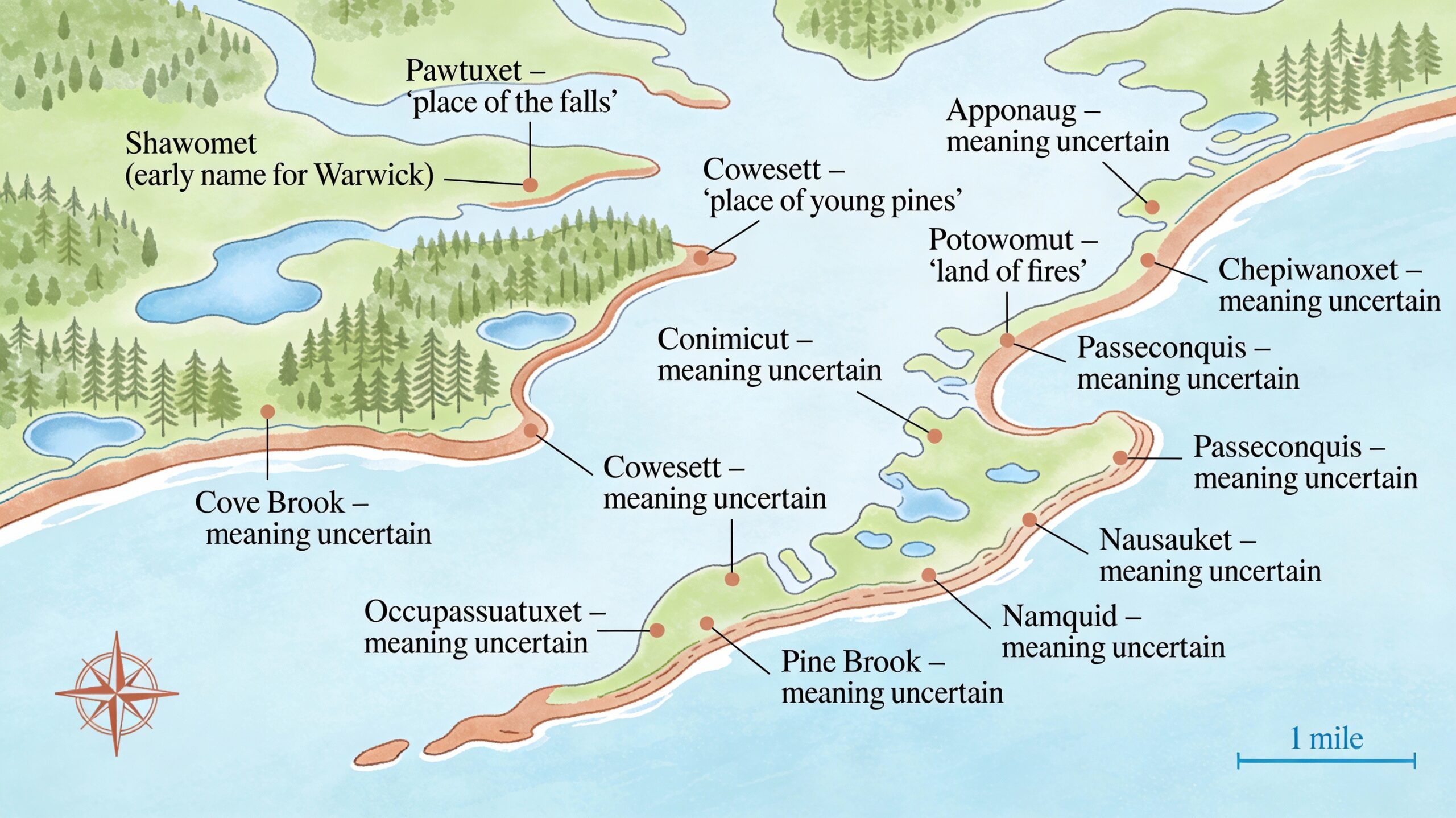

Cohost 1: We’re talking about Warwick’s relationship with its shoreline, which is so key to its identity.

Cohost 2: Exactly. And these two spots really show contrasting stories. You’ve got Goddard Memorial State Park bang, created as this active recreation spot back in the 20s.

Cohost 1: A memorial ready to go.

Cohost 2: And then there’s Rocky Point, nearly 150 years as this hugely popular private amusement park.

Cohost 1: An icon.

Cohost 2: Before it closed, fell apart, and eventually became this uh public green space much, much later. We’re going to follow that exact timeline.

Cohost 1: Highlighting the key decisions, the maybe the political angles, the dates that lock down these big chunks of Greenwich Bay and Narragansett Bay for everyone.

Cohost 2: We’re tracking that shift from inherited land and uh private fund zones into these large public areas.

Cohost 1: It really is a fascinating look at how public spaces actually get made. Sometimes it’s quick, like you said, a gift.

Cohost 2: And sometimes it’s a real slog, a public fight almost.

(…the conversation continues, alternating similarly as above, through both stories: the Goddard Memorial State Park donation and the journey of private to public at Rocky Point—with the speakers keeping to these roles.)

Cohost 1: So what’s the big takeaway here? The synthesis?

Cohost 2: I think the aha moment is that both stories are about preservation, but with different goals and frankly different costs. Goddard preserved nature for structured activity funded by philanthropy.

Cohost 1: Right.

Cohost 2: Rocky Point, after immense effort and public spending, preserved the fundamental right of access to the shore. It turned commercial entertainment back into just space of you, a walking path, secured by the taxpayers who voted for it.

Cohost 1: But in both cases, the end result was securing critical shoreline on Greenwich Bay and Narragansett Bay for public use, preventing it from being locked away privately.

Cohost 2: Exactly, hugely important outcome however different the journeys were.

Cohost 1: And that journey for Rocky Point, especially that 2000 Azar thesis, laying out the options, open space, housing, mixed use, reminds us that there were other very lucrative paths that land could have taken.

Cohost 2: Definitely. The choice for passive open space wasn’t the default, it was fought for.

Cohost 1: Okay, so given that history, given the debate and thinking about pressures today, population growth, development pressure on the coast in Rhode Island, here’s a final thought for you our listener to chew on.

Cohost 2: Mhm.

Cohost 1: Both parks provide vital public access. Rocky Point’s passive designation came from a mix of philosophy, cost, and environmental reality back then. But what about the future? What new community needs or maybe external pressures, think about climate change adaptation, maybe demands for renewable energy infrastructure like offshore wind connections, could eventually challenge that passive use label at Rocky Point.

Cohost 2: And if those pressures do arise, how might that affect the preservation of the land itself and those few fragile links to its past, the arch, the towers, the ruins? Something to think about.